Christopher Gannatti, CFA, Head of Research, Europe, WisdomTree Asset Management

We believe Japan is an interesting market, with many positive things occurring at the policy level and with very inexpensive and improving fundamentals.

Market participants outside Japan often don’t pay as much attention to Japan, because they think that the hype over Abenomics and the subsequent investment opportunity have both passed.

With Japan so far out of favor among investors, is it a contrarian opportunity, or are we continuing to be fooled by the false allure of Japan’s potential?

Mood Swings

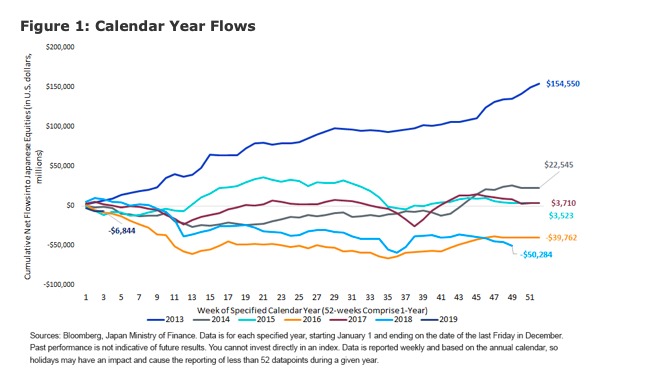

Going back to late 2012, it is true that Japan represented massive potential for reform and excitement that many viewed as almost certain to contribute to strong equity returns. Figure 1 indicates that:

Non-Japanese investors plowed nearly $155 billion into Japan’s equity market in 2013, based largely on the initial excitement of prime minister Shinzo Abe’s election and agenda, as well as the initiation of Japan’s own massive quantitative easing (QE) policy under the leadership of Bank of Japan (BOJ) governor Haruhiko Kuroda.

Since 2013, the pattern of foreign investor flows has become progressively more volatile. 2018 was the worst year of Prime Minister Abe’s tenure from an investor flow perspective, as foreign investors pulled more than $50 billion out of Japan’s equity market.

Investor Assumptions

While we’d like to think that each investor is studying Japan’s market, poring over financial data and becoming as excited as we are when Japan implements what we consider innovative tax and incentive policies (not to mention the central bank buying equities), the reality is different.

Japan has had substantial volatility during the Abenomics period (which started in December 2012), meaning investors could have caught Japanese equity exposure at the wrong time.

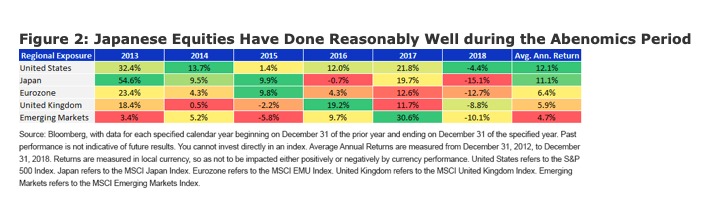

However, for comparative purposes, we frequently resign ourselves to using more standardized periods of time, such as calendar years. Figure 2 indicates:

Capital Flows

Last year, when more than $50 billion was taken out of Japan by foreign investors, we saw that Japan’s equity returns were poor, ranking behind the United States, the eurozone, the United Kingdom and even emerging markets.

As a result, outflows during that particular year made sense based on our behavioral assumption that poor performance correlates positively to investor outflows.

If we extend the horizon and look at the full period of Abenomics, calendar year by calendar year, based on investors’ sentiment about Japanese equities, we’d assume that Japanese stocks would be at the bottom of the pack. In 2016 and in 2018, Japanese equities were the worst performers of the regions we show.

Abenomics

But, importantly, in 2013 and in 2015, they were the top performing, and in 2014 and 2017, they were in the middle of the pack.

Even the U.S. equity market, viewed frequently as possessing unassailable performance supremacy in recent years, only led the other regions in two of those years.

During the full period, only two markets achieved double-digit returns. The U.S. equity market was at the top of the range, which likely surprises no one. Japan came in second, beating the eurozone, the United Kingdom and emerging markets. That, we would predict, surprised almost everyone.

Contrarian Play

Of course. But the possibility would be true for any contrarian investment. In a way, the definition implies that the consensus view would be for further negative returns.

One of WisdomTree’s core principles is that valuation matters. Unfortunately, the data doesn’t suggest that valuation always matters equally across all markets, because nothing in investing is that simple.

On the other hand, trying to say “valuation doesn’t matter” leaves one back in the U.S. tech sector in 1999 and 2000, when suddenly it did matter in a big way.

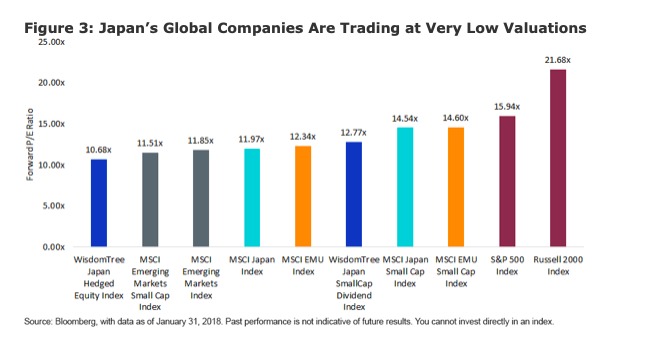

In figure 3, we see that the risk of Japan’s largest and most global companies could be close to being “priced in,” likely due to uncertainty surrounding global trade tensions and a challenging domestic market environment.

As a result, Japan’s forward P/E ratio is at about two-thirds that of the S&P 500 Index. The risks of emerging markets, for example, are widely known, yet these businesses are trading at even lower valuations.

Takeaway

There is no question that Japan and Japanese equities are hard allocations to position today.

There is also no question that most investors are not focusing on Japan right now.

This tells us that there is an opportunity for a surprise in 2019.

And surprises to the consensus have historically been some of the best return opportunities.

Photo Credit: Alejandro via Flickr Creative Commons

Disclosure: Certain of the information contained in this article is based upon forward-looking statements, information and opinions, including descriptions of anticipated market changes and expectations of future activity. WisdomTree believes that such statements, information, and opinions are based upon reasonable estimates and assumptions. However, forward-looking statements, information and opinions are inherently uncertain and actual events or results may differ materially from those reflected in the forward-looking statements. Therefore, undue reliance should not be placed on such forward-looking statements, information and opinions.