By: Jose Torres, Interactive Brokers’ Senior Economist

Consumer Spending Slows While the Fed Is Still Hiking

The Federal Reserve’s aggressive monetary policy tightening is slowly helping to moderate inflation, but it has a long way to go to tame price increases in the sticky services components which will likely require further slowing in the labor market. Bank failures in mid-March have led to investors expecting a much more dovish Fed in 2023, however, as they predict that the central bank will increasingly consider financial stability alongside its 2% inflation target. Wage pressures remain strong driven by a tight labor market and consumption is slowing while GDP growth is weakening. Monetary policy operates with long and variable lags and is likely to weigh further on consumer spending and economic activity later this year as 475 basis points of interest rate hikes with the possibility of more on the way are digested. These factors point to growing risks of the economy lapsing into stagflation, an environment of slower economic growth alongside higher than trend inflation.

The rate of overall inflation remains high but has moderated against the backdrop of slowing consumption and tighter financial conditions. The Federal Reserve’s (the Fed) preferred gauge of inflation, the core PCE, is at 4.6% as of March, almost two and a half times the Fed’s 2% target. The Fed is likely to continue raising the federal funds rate from its 4.88% level in order to dampen inflationary pressures, consistent with its Summary of Economic Projections. The Fed’s projections imply a terminal rate of 5.13% and no rate cuts for the rest of the year but market participants don’t think the economy and markets can handle that. Odds favor interest rate cuts during the 4th quarter of this year while the move at the May meeting carries an 92% probability of a 25-basis point hike and 8% odds of a pause. Market expectations have shifted meaningfully since the middle of March, as bank failures have led to the marketplace forecasting faster rate cuts against the backdrop of a Fed that they think will increasingly consider financial stability alongside its inflation mandate.

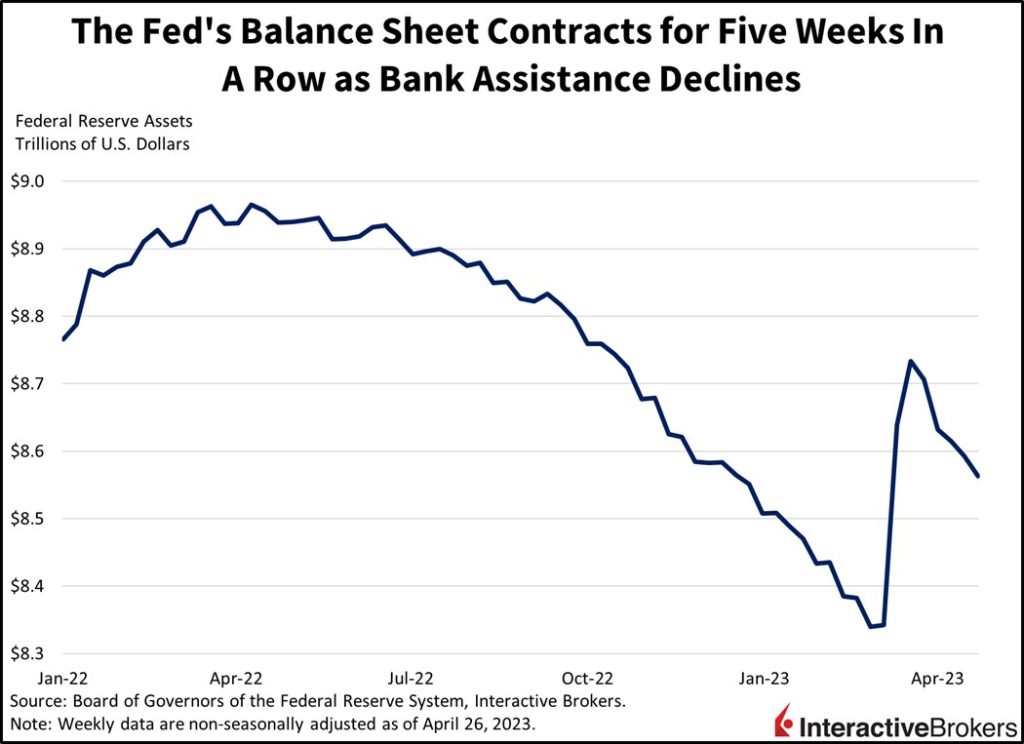

In addition to rate hikes, the Fed has increased the pace of its balance sheet reduction program to a monthly cap of $95 billion from $47.5 billion in the prior months, further constraining the money supply and financial conditions alike. During the two weeks ending March 22nd, however, bank troubles led the Fed to inject $392 billion into the economy, a result of the emergency Bank Term Funding Program. While the emergency program is in place for at least one year, it’s unclear how much more the banks will use the program as Fed efforts to help the banking sector offset the progress made on its inflation mandate. The Fed has expressed a strong commitment of keeping rates higher for longer until it sees convincing evidence of inflation returning to the 2% target, even as economic conditions continue to deteriorate. Tighter lending conditions at banks in the aftermath of the March scares are also likely to weigh on economic and employment growth. The week ending March 22nd featured the sharpest contraction in lending and deposits since the 2008 financial crisis. Lending conditions and deposits have stabilized somewhat, as liquidity from the Fed served to suppress bond yields, capitalize bank balance sheets and calm depositor concerns.

Leading economic indicators point to 2nd quarter GDP growth of -0.2%.

Below, we examine what leading economic indicators portend to our picture of the evolving economic landscape. This is our view at the moment and our projections may be confirmed or we may have to adjust them as different, new information, including freshly released economic indicators, are made available.

Initial Unemployment Claims

With the Fed aggressively hiking interest rates and consumer spending slowing, the labor market is showing initial signs of softening. Initial unemployment claims have risen sharply in the last few weeks against the backdrop of slower revenue growth, persistent cost pressures, weakening margins, declining profitability and tighter financial conditions. The tech sector specifically has laid off more than 349,000 workers in 2022 and 2023 while banks and certain companies in other sectors have also implemented layoffs and hiring freezes. Some companies, however, are hoarding labor due to difficulties with hiring during the pandemic and the current labor shortage resulting, in large part, from historically low labor force participation. The low participation rate results in large part from Americans retiring early during the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, discouraged workers upset about income and growth prospects, a skills mismatch as companies struggle to match job openings with job applicants and to a lesser extent from working age Americans on the sidelines due to long-haul Covid. Participation has climbed for four consecutive months however, as Americans flock back to the labor force for income to offset the adverse pressure of persistent inflation and elevated financing costs. Still, labor force participation remains well below pre-pandemic levels.

We expect the economic slowdown, tighter credit conditions and higher interest rates to lead to modestly higher unemployment in 2023 as tighter monetary policy gets digested, financial conditions tighten and pandemic-era savings become depleted. Fiscal stimulus has been limited in 2023 and 2022 compared to 2021 and 2020 while persistent inflation has emerged as a new generational headwind, slowing consumer spending. During times of monetary policy tightening and higher interest rates, business revenue tends to slow because financing the production of goods and services becomes more expensive, leading to possible layoffs as businesses attempt to sustain profit margins. An increase in initial unemployment claims would point to the following changes: lower consumption/demand, lower inflation, lower long-term interest rates and lower GDP growth. If initial unemployment claims drop significantly, demand will rise, inflation will rise, long-term interest rates will rise and GDP growth will rise. The next unemployment release will be on May 4th. It is currently expected to be 240,000, an increase from the previous week’s reading of 230,000. Should the actual number be much lower or higher, we would have to adjust our outlook by slightly raising or lowering our estimate for economic indicators and ultimately our estimate for GDP.

Retail Sales

Consumers are slowing their spending as economic conditions weaken. This slowdown is occurring against the backdrop of tighter financial conditions, higher prices and reduced job openings. After growing rapidly during most of the past three years due to support from strong monetary and fiscal stimulus, retail sales have slowed and when accounting for inflation, have contracted in many recent months. This trend is especially true with goods, with some recent gauges of manufacturing activity showing the sharpest contractions since the heights of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020.

Consumer spending is likely to slow further as pandemic-era savings dwindle, labor market opportunities lessen and the Fed continues to tighten credit conditions and raise rates, dampening demand, especially for big ticket items. Fiscal stimulus has been limited in 2023 and 2022 compared to 2021 and 2020 while persistent inflation has emerged as a new generational headwind, constraining consumer spending on a relative basis. During times of monetary policy tightening and higher interest rates, consumption tends to slow because goods and services become more expensive to finance. A continued slowing or contraction of retail sales would point to the following changes: lower consumption/demand, lower inflation, lower long-term interest rates and lower GDP growth. If retail sales growth ramps up again due to monetary policy easing, consumption/demand will rise, inflation will rise, short-term interest rates will fall and GDP growth will rise. The next month’s release will be on May 16th. It is currently expected to decline to $679.63 billion, a 0.5% month-over-month drop, a slower rate of decline from the previous month’s $683.04 billion, a 0.6% fall from February. Should the actual number be much lower or higher, we would have to adjust our outlook by slightly raising or lowering our estimate for economic indicators and ultimately our estimate for GDP.

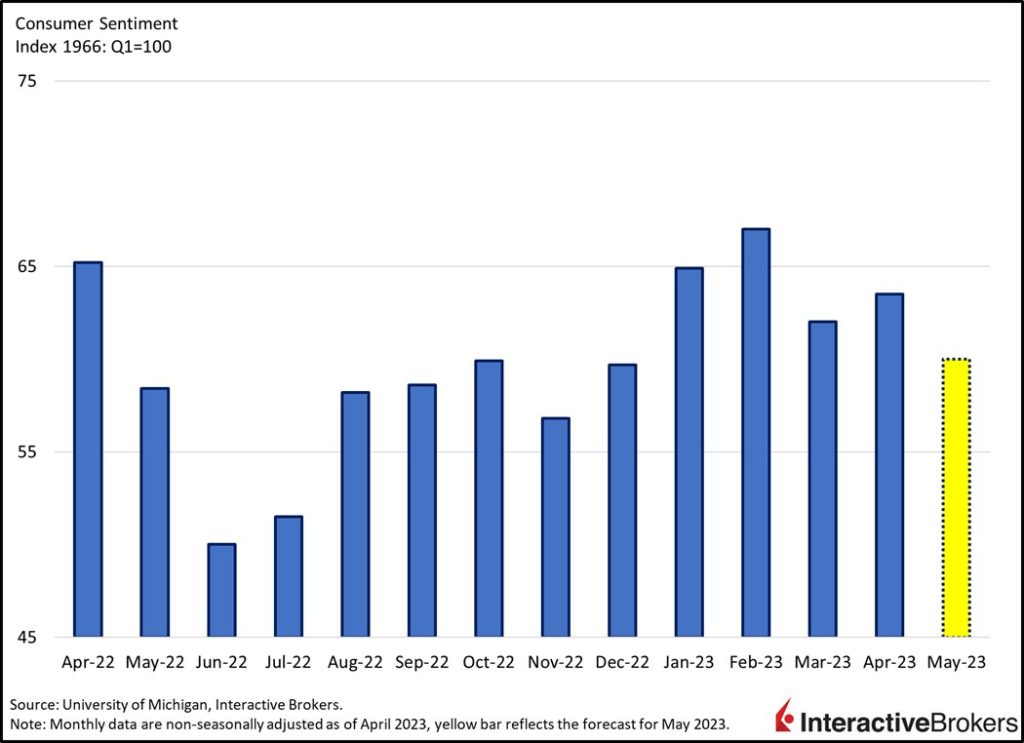

Consumer Sentiment

Consumer sentiment is bouncing along low levels as financial conditions tighten, labor market opportunities wane and inflation persists. Sentiment was high for much of the past three years supported by strong monetary and fiscal stimulus, but it has weakened significantly. Since June 2022 however, consumer sentiment has found a floor in recent months, driven by falling gasoline prices and stabilizing interest rates although it remains at historically low levels still. Fiscal stimulus has been limited in 2023 and 2022 compared to 2021 and 2020 while persistent inflation has emerged as a new headwind, weakening consumer sentiment on a relative basis. During times of monetary policy tightening and higher interest rates, sentiment tends to weaken because employment conditions and business revenue growth generally soften while goods and services become more expensive to finance, hampering consumers. Continued low levels of consumer sentiment would point to the following changes: lower consumption/demand, lower inflation, lower long-term interest rates and lower GDP growth. If consumer sentiment ramps up again due to monetary policy easing, consumption will rise, demand will rise, inflation will rise, short-term interest rates will fall and GDP growth will rise. The next month’s release will be on May 12th. It is currently expected to be 60, declining from the previous month’s reading of 63.5, an increase from March’s 62 level. Should the actual number be much lower or higher, we would have to adjust our outlook by slightly raising or lowering our estimate for economic indicators and ultimately our estimate for GDP.

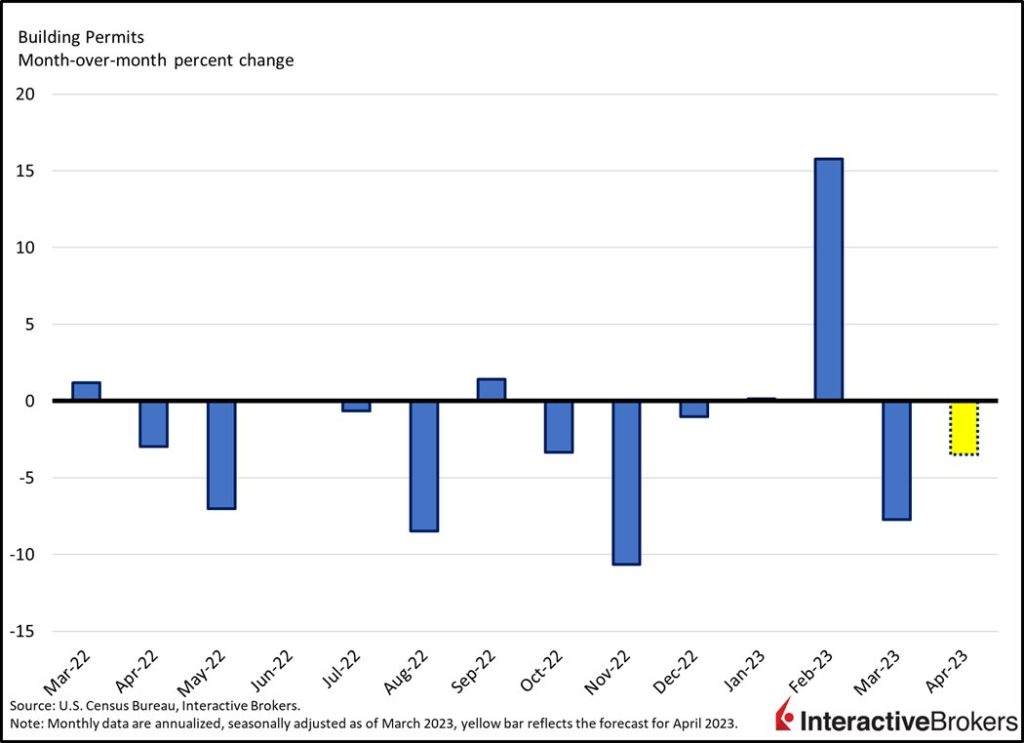

Building Permits

The real estate industry is weakening dramatically under the weight of near all-time low home affordability driven by high prices and high mortgage rates. Building permits are falling against the backdrop of tighter financial conditions and a lack of homebuyers. After growing at a strong level for most of the past three years, supported by strong monetary policy stimulus and an increased demand for housing outside of urban areas due to the pandemic, building permits have slowed and are now in contraction territory. Expectations of further slowing is expected as the Fed continues to tighten credit conditions and raise rates, slowing demand in this capital intensive, economically cyclical, interest-rate-sensitive industry. Significant home price growth has pressured affordability to near its worst level in history, leading to significant contractions in mortgage applications and a significantly higher share of rental apartment construction. During times of monetary policy tightening and higher interest rates, building tends to slow because real estate becomes much more expensive to finance. A continued contraction in building permits would point to the following changes: lower consumption/demand, lower inflation, lower long-term interest rates and lower GDP growth. If building permit growth ramps up again due to monetary policy easing, demand will rise, inflation will rise, short-term interest rates will fall and GDP growth will rise. The next month’s release will be on May 17th. It is currently expected to come in at 1.38 million seasonally adjusted annualized units, a 3.5% decline from the previous month’s 1.43 million, which was a 7.7% decline from February. Should the actual number be much lower or higher, we would have to adjust our outlook by slightly raising or lowering our estimate for economic indicators and ultimately our estimate for GDP.

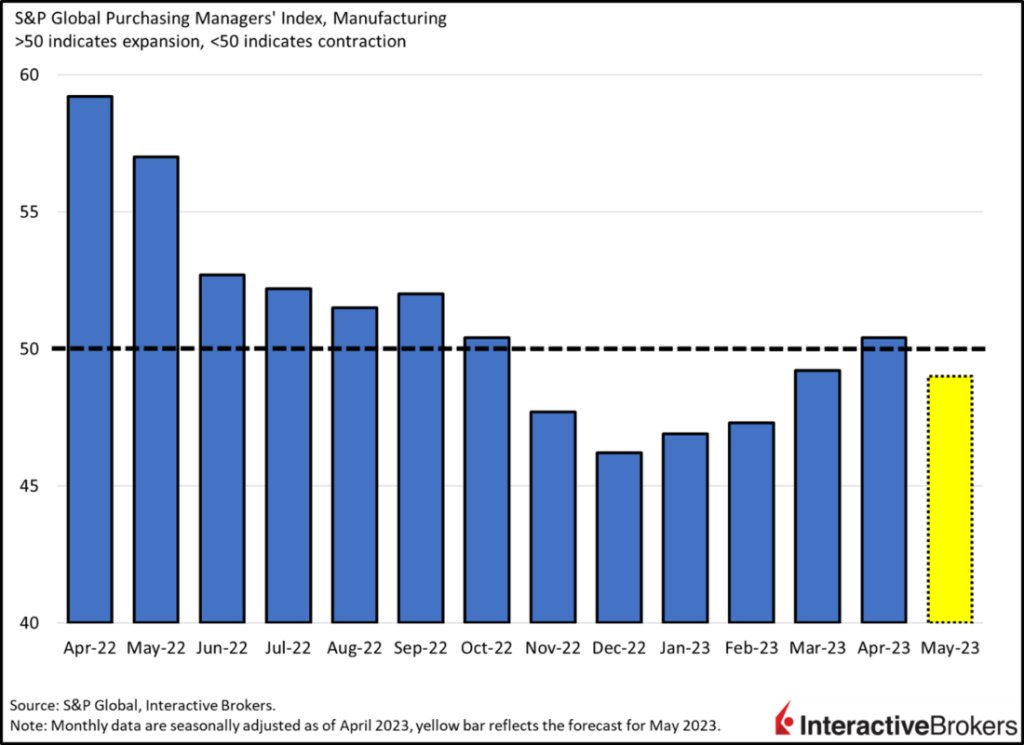

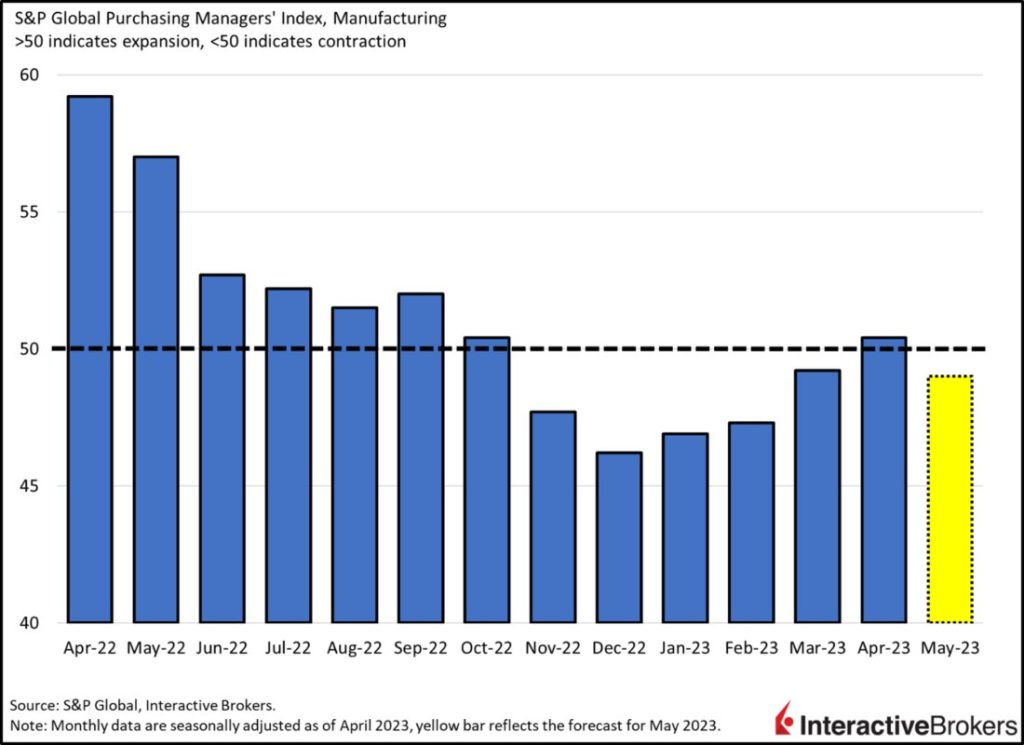

PMI-Manufacturing

Tighter financial conditions and slowing consumption are contributing to sharp declines in manufacturing activity. After expanding at a strong level for much of the past three years, supported by strong monetary and fiscal policy stimulus and increased demand for manufactured goods rather than services due to the pandemic, manufacturing activity has been in contraction territory for most of the past few months. New orders, the largest component of the PMI, has weighed the most on the headline figure, signaling depressed demand for big ticket items, historically a leading indicator of not just the manufacturing sector, but of the entire economy. Expectations of continued slowing is expected as the Fed continues to tighten credit conditions and raise rates, slowing demand in this capital intensive, economically cyclical, interest-rate-sensitive industry. During times of monetary policy tightening and higher interest rates, manufacturing tends to slow because manufactured, durable goods like furniture, automobiles, airplanes and factory equipment become much more expensive to finance while loan qualification standards increase and employment conditions deteriorate. A continued contraction in manufacturing activity would point to the following changes: lower consumption/demand, lower inflation, lower long-term interest rates and lower GDP growth. If manufacturing activity ramps up again due to monetary policy easing, demand will rise, inflation will rise, short-term interest rates will fall and GDP growth will rise. The next month’s release will be on May 23rd. It is currently expected to be 49, a decline from the previous month’s reading of 50.2, shifting back into contraction territory. Should the actual number be much lower or higher, we would have to adjust our outlook by slightly raising or lowering our estimate for economic indicators and ultimately our estimate for GDP.

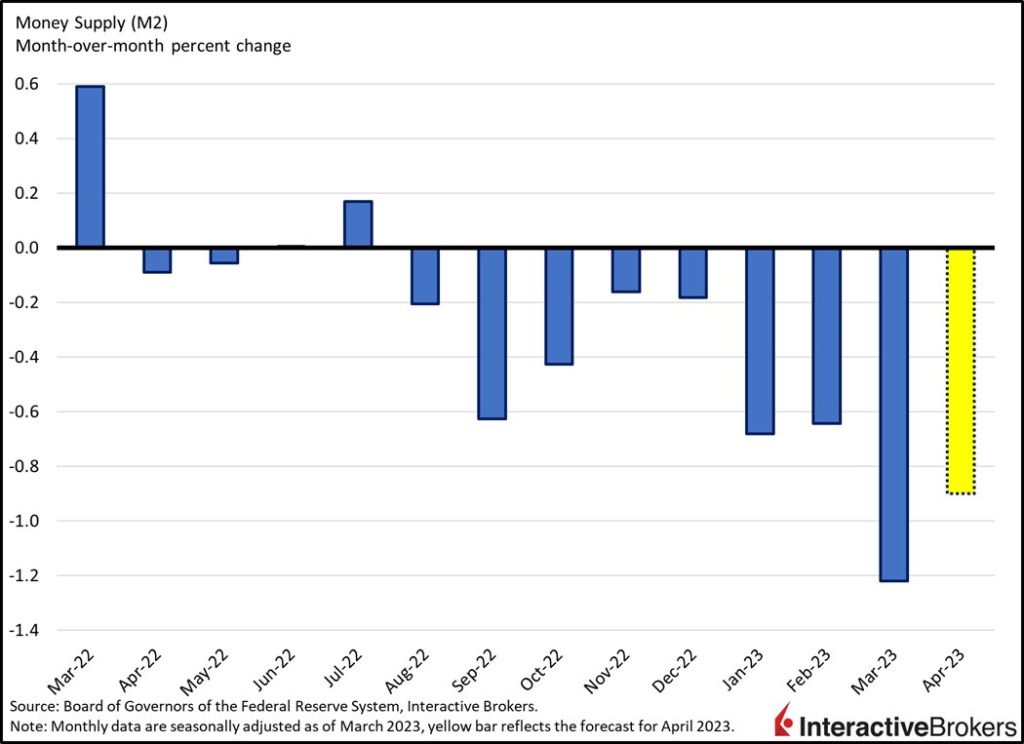

Money Supply

The rates of inflation and economic growth are weakening against the backdrop of a contracting money supply. The money supply, inflation and economic growth shift a great deal due to the Fed’s monetary policy. After increasing drastically since the emergence of COVID-19 to help businesses and households cope with pandemic disruptions, the money supply has contracted from its April 2022 peak. The Fed has pivoted from an accommodative monetary policy stance towards a restrictive one because it recognizes that money supply growth during years 2020 and 2021 contributed to today’s high inflation. The more persistent inflation ends up being, the longer the Fed will have to maintain a restrictive position and therefore, limit money supply growth. At this point in time, the aggregate money supply is contracting because the Fed has a long road of tightening ahead in order to achieve the 2% inflation target. The Fed has embarked on an aggressive rate hiking campaign and has increased the pace of balance sheet reduction to a monthly cap of $95 billion from $47.5 billion in the months prior. While events in March led to a balance sheet increase, the balance sheet has contracted significantly for five consecutive weeks as the banking sector stabilizes somewhat. Significant risks concerning sharper contractions in the money supply may manifest if there are more bank failures later this year. If uninsured deposits are destroyed due to constraints related to the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund and the U.S. Treasury’s budget, the decline in larger deposits will weigh heavily on the money supply. A contraction in the money supply would point to the following changes: lower consumption/demand, lower inflation, lower long-term interest rates and lower GDP growth. If money supply growth ramps up again due to monetary policy easing, consumption will rise, demand will rise, inflation will rise, short-term interest rates will fall and GDP growth will rise. The next month’s release will be on May 23rd. It is currently expected to decline to $20.63 trillion, a 0.9% month-over-month decline from the last month’s $20.82 trillion, which was a 1.2% decline from February. Should the actual number be much lower or higher, we would have to adjust our outlook by slightly raising or lowering our estimate for economic indicators and ultimately our estimate for GDP.

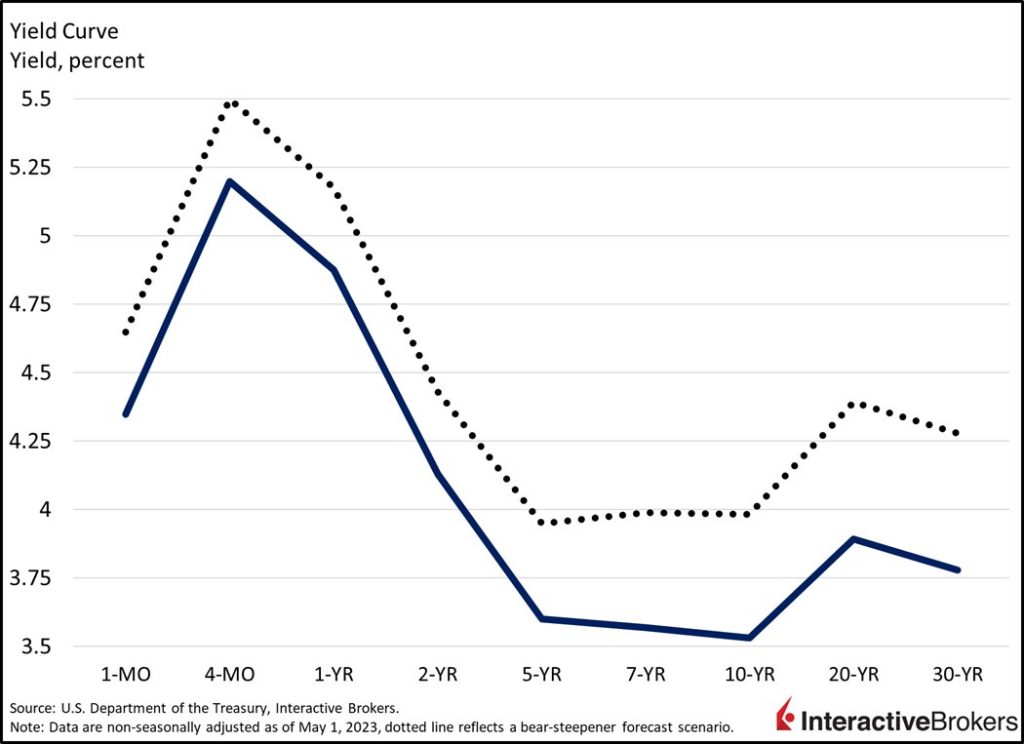

Yield Curve

The yield curve is severely inverted against the backdrop of tighter financial conditions and weak economic prospects. As the 2-year yield rose much faster than the 10-year since January 2022, a bear-flattening move from a much steeper level from the previous two years, the yield curve remains in deep inversion territory (-54 bps), signaling economic contraction ahead. The money supply increase led to a rise in inflation which compelled the Fed to raise short-term rates significantly. The longer end of the curve, the 10-year maturity, didn’t rise as fast because longer term economic growth and/or inflation isn’t expected to rise as strongly as short-term rates did. The yield curve inversion is telling us that there’s little chance the U.S. economy can handle the monetary policy tightening that’s in the pipeline without a recession. In this case a bull-flattener, where the 2-year would fall slower than the 10-year would be desirable but that would require inflation expectations to significantly come down further, which is unlikely to occur. Although inflation expectation figures are off their peaks, we believe inflation will prove stickier and more resilient than the market thinks. Against the backdrop of persistent core inflation and a tight labor market, the expectation in the coming months is to see a bear-steepener where the 10-year widens its spread against the 2-year due to an increase in inflation expectations. The main drivers of structurally higher inflation in the medium to long-term are the shift from globalization towards regionalization, geopolitical tensions, relative inefficiencies regarding supply chains and the commodity complex, continued deficit spending and labor shortages. Another headwind concerning rates in the short-term is Congress’s debt ceiling showdown, which will injure economic activity and financial markets if an agreement isn’t secured in the next few weeks. Already, there’s an 80-basis point inversion between the 1- and 2-month Treasury Bill yields, as investors feel much safer over 1 month than they do 2 months out. If the yield curve remains severely inverted, it points to lower consumption, lower demand, lower inflation, lower long-term interest rates and lower GDP growth. If the yield curve steepens again due to monetary policy easing, demand will rise, inflation will rise, short-term interest rates will fall and GDP growth will rise. The yield curve inversion (2s, 10s) has predicted the last 6 out of 6 recessions.

Economic Indicators & The Economy

Below is a picture showing how leading, coincident and lagging economic indicators reflect household, business and government activity. Leading indicators provide early signals of future economic health while coincident and lagging indicators confirm the economic trend in later periods.

This post first appeared on May 1st 2023, Traders’ Insight Blog

PHOTO CREDIT: https://www.shutterstock.com/g/Bobex-73

Via SHUTTERSTOCK

DISCLOSURE: INTERACTIVE BROKERS

Information posted on IBKR Campus that is provided by third-parties and not by Interactive Brokers does NOT constitute a recommendation by Interactive Brokers that you should contract for the services of that third party. Third-party participants who contribute to IBKR Campus are independent of Interactive Brokers and Interactive Brokers does not make any representations or warranties concerning the services offered, their past or future performance, or the accuracy of the information provided by the third party. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This material is from IBKR Macroeconomics and is being posted with permission from IBKR Macroeconomics. The views expressed in this material are solely those of the author and/or IBKR Macroeconomics and IBKR is not endorsing or recommending any investment or trading discussed in the material. This material is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security. To the extent that this material discusses general market activity, industry or sector trends or other broad based economic or political conditions, it should not be construed as research or investment advice. To the extent that it includes references to specific securities, commodities, currencies, or other instruments, those references do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold such security. This material does not and is not intended to take into account the particular financial conditions, investment objectives or requirements of individual customers. Before acting on this material, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, as necessary, seek professional advice.

In accordance with EU regulation: The statements in this document shall not be considered as an objective or independent explanation of the matters. Please note that this document (a) has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research, and (b) is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination or publication of investment research.

Any trading symbols displayed are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to portray recommendations.