By Liqian Ren Director of Modern Alpha

If narratives are how human beings make sense of the world, then narratives are how most people made sense of China in 2021.But like many stories, the China narratives require context.

Here are my attempts to help sort through which China narratives are overhyped and which are underappreciated.

First, let’s look at the most overhyped narratives.

1. Common prosperity means the government taking money from private entrepreneurs and businesses.

This is the most hyped China narrative. There is one province, Zhejiang, in the well-off east coast, set up as an experiment for common prosperity goals.

Most of the actual policy goals are related to fostering high-quality economic growth, increasing access to childcare and elderly care and lowering employment barriers like gender or household registration discrimination. Most would be considered standard social welfare in the west, which China lacks.

BABA and Tencent donated substantial money for “charitable” purposes, answering the government’s call for common prosperity. But many of those donations are geared toward helping the donor company’s own business area. BABA’s charity support for rural e-commerce is directly helpful to its fierce competition with Pinduoduo, another upcoming e-commerce challenger.

There is local skepticism that pledged donations are investments in disguise. Tencent stated its donations are for rural improvement, low-income groups, health infrastructure and education. Not many noticed that amid an edu-tech crack down, Tencent has positioned itself as the responsible provider of education services.

2. China cracked down on Ant Financial/BABA

Ant Financial’s IPO was abruptly halted by the government, which sparked many headlines starting, “China cracks down…”

As we’ve written about extensively, and mentioned on a podcast on Ant’s business lines, it’s obvious this is more a case of China trying to catch up on fintech regulation with a huge company with systemic financial risk. Fintech is an area where China and most emerging markets are ahead of developed markets, paradoxically due to the weak landline, banking and credit card financial structure. Emerging markets leapt to mobile fintech to start. Ant deploys very high leverage and predatory lending, mixed payment with lending businesses with no financial regulations. These fintech regulations would have caught up with Ant, if not during the IPO process, then after.

3. China cracks down on Meituan/controls the Tiktok algorithms

These narratives are both related to protecting workers and consumers in a platform economy.

In the Meituan case, the issue was how much labor protection food delivery workers should enjoy, and whether they are employees or contractors.

With Tiktok, similar to Facebook, the issue is how much say the government has with regard to its algorithms, which influence what our kids read, how they entertain themselves and organize their social lives. How much of a nanny state will China be?

The interaction of regulations and businesses are at the forefront of the metaverse. Due to its early entrance in the mobile and digital economies, China struggles with how to regulate this area. There will be regulations that might seem uniquely Chinese today, but may not be as the world moves more into digital life.

The risk here, always, is over-regulation that chokes business innovation. But many of the actual regulations so far are not like the narratives paint them, like it’s moving toward a 1984-style government control.

4. Chinese companies’ VIE structure is to defraud foreign investors.

The variable interest entity (VIE) structure is what firms use to get around Chinese foreign ownership control on education, media, telecommunication and derived e-commerce.

A Chinese lawyer with experience in China’s Ministry of Justice and western capital markets came up with the idea because he understood the fine line where businesses could innovate and flourish without being called illegal.

China benefited immensely from this structure.

Even VIE is de facto illegal if interpreted according to the words of Chinese law, the Chinese government has never stated so. Recently, it actually moved to allow VIE companies to list in Chinese stock exchanges, folding them into the regulatory framework by treating them as equal to other Chinese firms.

VIE Chinese firms will face more regulation, like other non-VIE Chinese firms, such as requiring approval to list which current VIE firms have used the loophole, as with DIDI. But this equal-status fact itself means it has achieved de-facto legal status in China.

5. Taiwan conflict risk has increased significantly

Every October, when China’s mainland and Taiwan both have national day celebrations, the media always publishes articles that suggest the risk of conflict has substantially increased. Together with China being a bipartisan, negative topic in the U.S., the discussions can be extremely charged.

However, politicians in the U.S., mainland China and Taiwan played along during the Taiwan discussions, so it diverted domestic attention from internal problems. Taiwan has an important December referendum on four big domestic issues that are likely to see the current party and president lose significantly. Politics are local. The key to Taiwan’s conflict is its domestic politics, which has been the missing piece.

Now here are two narratives where the contexts are under reported.

1. China cracked down on under-18 academic tutoring but quietly acknowledged its clumsy policy-making process. If there is one regulation that’s a real crackdown, the education regulation is fitting.

Even though there were some signals that the government and the Chinese public are increasingly uncomfortable with widespread private academic tutoring services, the way it was handled was clumsy.

One week after the education regulation only allowing non-profit private academic tutoring for under-18 education, the Minister of Education was relieved of his main party secretary title and officially relieved of duty, after only a month on the job.

Two other related news angles are also underreported. After China experienced an energy crunch, Chinese regulators worked to mobilize coal production. It also quietly directed fewer environmental top-down policies. The other is Evergrande, and the Chinese real estate saga.

In January 2020, rules limiting banks’ exposure to developers and household mortgages officially start, together with monitoring of real estate firms’ debt-to-equity, cash on hand and debt-to-asset ratios.

This, coupled with Evergrande’s own financial mismanagement, contributed to a significant decline of capital to the whole real estate sector. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) was quick to realize the potential contagion risk and worked behind the scenes to loosen credit.

China’s challenge is enacting top-down centralized policies without choking off growth. The government’s follow-up responses on education, energy and real estate do show that some feedback from local economic conditions to the central government got through. They seemed imperfect to people who are used to a more open and predictable legal and political process. But if these feedbacks were not in existence, it would be hard to be optimistic about China equities.

2. Chinese central bank and continued reluctance on financialization to stimulate the economy

China’s central bank, PBOC, is underreported.

Most articles on China focus on the Chinese government’s role, even though most Chinese work for private businesses. The media has also shed little light on PBOC’s decision-making.

PBOC is part of the Chinese government’s executive branch, so its independence is limited and its goal is never central bank policy independence.

Its goal has been to limit systemic financial risk onshore with flexible and stable FX for the Chinese currency. Its track record in the last five years is considered good enough to have earned credibility with both onshore and offshore investors.

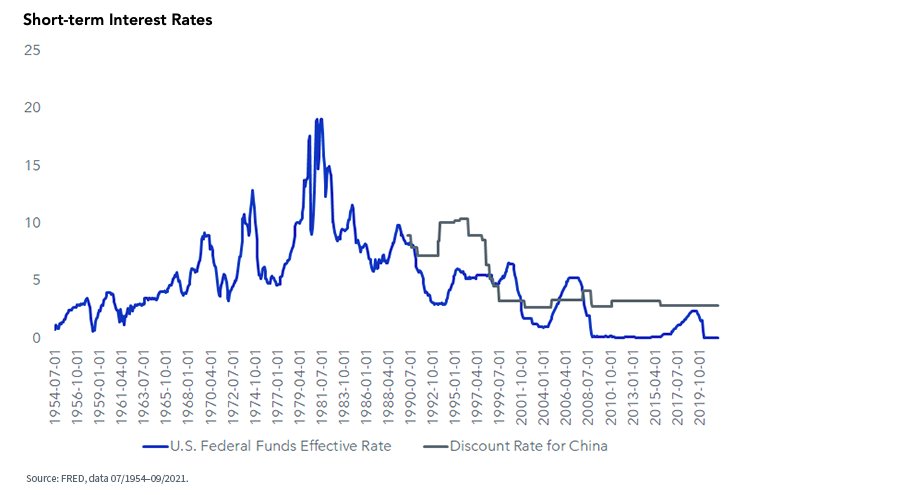

China’s monetary policy to stimulate the economy will always be the second fiddle to fiscal policy. That’s why PBOC is unlikely to enact dramatic monetary policy like the Federal Reserve, even the high interest rate difference between China and the U.S. gave it ample monetary tools, as shown below.

Short-term Interest Rates

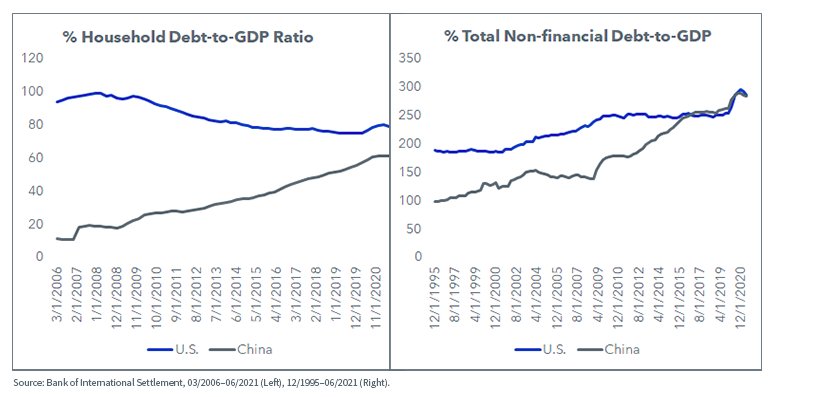

There is a very strong narrative in China that the U.S.’s problem is financialization of the economy, evidenced by the 2008 financial crisis. Whether that narrative is valid or not is beside the point as China is adamant to not allow high leverage in its economy.

The dramatic rise of Chinese household debt in the last 20 years, even though still lower than in the US, has made Chinese policy makers very wary of taking on more debt to stimulate economic growth. In this context, fintech will continue to be highly regulated, the real estate sector will continue to be restrained, and the Chinese economy is likely to be growing in the lower range of PBOC’s 5%–6% potential growth target, closer to 5%.

Conclusion

In summary, the place to pay attention is still Chinese growth, the sectors and companies that can generate profit and grow, in a macro environment that still focuses on growth, but that is not friendly to growth driven by financial leverage.

This post first appeared on December 21 on the WisdomTree blog.

Photo Credit: gags9999 via Flickr Creative Commons

DISCLOSURE

There are risks involved with investing, including possible loss of principal. Foreign investing involves currency, political and economic risk. Funds focusing on a single country, sector and/or funds that emphasize investments in smaller companies may experience greater price volatility. Investments in emerging markets, currency, fixed income and alternative investments include additional risks. Please see the prospectus for discussion of risks.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. This material contains the opinions of the author, which are subject to change, and should not to be considered or interpreted as a recommendation to participate in any particular trading strategy, or deemed to be an offer or sale of any investment product and it should not be relied on as such. There is no guarantee that any strategies discussed will work under all market conditions. This material represents an assessment of the market environment at a specific time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events or a guarantee of future results. This material should not be relied upon as research or investment advice regarding any security in particular. The user of this information assumes the entire risk of any use made of the information provided herein. Neither WisdomTree nor its affiliates, nor Foreside Fund Services, LLC, or its affiliates provide tax or legal advice. Investors seeking tax or legal advice should consult their tax or legal advisor. Unless expressly stated otherwise the opinions, interpretations or findings expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of WisdomTree or any of its affiliates.

The MSCI information may only be used for your internal use, may not be reproduced or re-disseminated in any form and may not be used as a basis for or component of any financial instruments or products or indexes. None of the MSCI information is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such. Historical data and analysis should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of any future performance analysis, forecast or prediction. The MSCI information is provided on an “as is” basis and the user of this information assumes the entire risk of any use made of this information. MSCI, each of its affiliates and each entity involved in compiling, computing or creating any MSCI information (collectively, the “MSCI Parties”) expressly disclaims all warranties. With respect to this information, in no event shall any MSCI Party have any liability for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, punitive, consequential (including loss profits) or any other damages (www.msci.com)