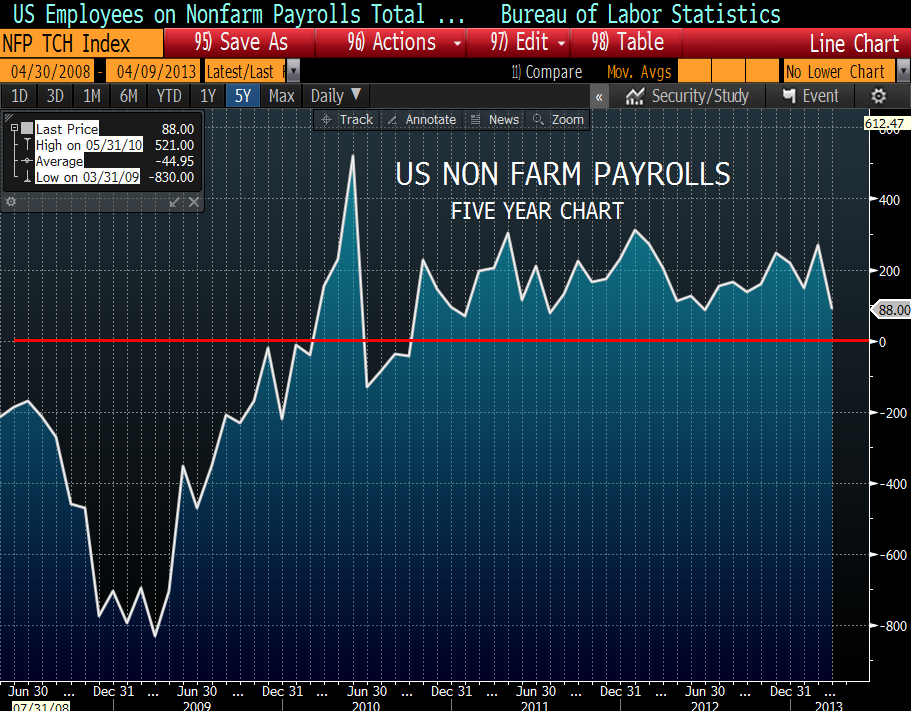

Once again we prefer to move quickly past the US employment report and recap a well told tale: Last week the US weekly unemployment claims were up, earlier the ADP National Employment Report private payroll numbers were below expectations, and the monthly employment numbers were bad.

The number of non-farm jobs created was 100,000 below the Wall Street consensus forecast, the average hourly earnings were down, and nearly half a million workers stopped looking for work. The labor force participation rate, i.e., the share of Americans ages 16 and over in the labor force, fell from 63.5% to 63.3% (a 34-year low) on a month-to-month basis.

Meanwhile, the number of Americans on permanent federal disability continues to climb; this appears to happen magically as soon as state unemployment benefits run out. This should drive the point home that just when we think we might be climbing out of the employment sinkhole, we learn that we are not.

Chart Courtesy of Bloomberg

One of the goals when creating the Euro was to simplify doing business within the European bloc of nations. In my opinion, the idea of requiring multiple currencies in an area the size of the US East Coast just didn’t make good business sense.

The cross currency situation could easily mean a job or project, having been bid out, with costs and profits carefully calculated, going horribly wrong. Imagine running a business and then some unrelated situation drives the Escudo/Mark or the Peseta/Franc exchange rate down enough to make the whole deal a wash.

Additionally, travelling within the European Union was always fraught with currency problems: do I have enough Francs, Marcs, Lira to get a cab from the train station to the hotel? This obviously created unwelcome pitfalls for tourists, maybe not a situation that discourages international travelling, but in my opinion, it certainly left a bad taste in your mouth.

I believe that the common currency was a logical first step to modernizing trade and regulations across European countries and attempting to put everyone on the same, level playing field. After a difficult start, things seemed to settle in, despite the prospect of 300 year old rivals establishing a common currency. After 10 years, it looked like it was holding together.

Even post-financial crisis, the economic climate seemed to be settling down until the Fall of 2011. Last summer, the President of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, came to the Euro’s defense and again seemed to quiet the situation.

Enter Cyprus and its collapsing banks, over-stuffed with Russian depositors and then over-invested in Greek securities. Banks borrow short-term and lend long-term, earning a spread in the process. But when the securities they buy in lieu of long-term loans are long-term Greek debt – Houston we have a problem.

German Chancellor Merkel stood sternly by and force fed a deal to Cyprus that spared smaller depositors but resulted in a haircut (charged a fee) for large depositors, all for the sake of a non-taxpayer funded European bailout of the Cypriot banks.

In addition, severe capital controls were “temporarily” implemented. This obviously helped the political stature at home but seriously opened (closed?) the barn door for potential or would be European investors. A short while later, the Dutch finance minister seemed to gloat that this was a deal that could be used again.

He quickly recanted the comments, but was he referring to Italy, Spain, or Portugal? After all, isn’t a Euro on deposit in any country in the European Union supposed to be equal? So a Cyprus Euro deposit shouldn’t be any different than a Euro deposit in Germany – until now. Good luck with that; we don’t think we will be opening any European bank accounts soon.

From Bloomberg, about the Cyprus deal: “By imposing capital controls, Cyprus has detached itself from Europe’s monetary union. A euro deposited in a bank in Cyprus is no longer worth the same as one deposited in France or Germany. It can’t be easily withdrawn, spent or converted, and is therefore a second-class euro.

The consequences are going to be harsh, with some economists now warning of Greek-like shrinkage of Cyprus’s gross domestic product. As long as capital controls are in force, no one is going to buy Cypriot government or corporate debt, or make direct investments in Cypriot businesses.”

Chart courtesy of Bloomberg.

Meanwhile, David Stockman has written a new book and hit the road touring and touting The Great Deformation. Clearly David has an impressive resume – Harvard Graduate School, four-year Congressman, and director of the Office of Management and Budget for President Ronald Reagan. He spent time at Salomon Brothers, Blackstone Group, and started his own private equity company: Heartland Industrial Partners.

Essentially, Stockman feels the American taxpayers got sold a bill of goods by Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, a former Goldman Sachs Chairman. Certain companies should have been left to go out of business, but instead they got government support. He feels the hysteria was stirred up, in part by those who had vested interests and later made multiple million dollar bonuses.

Essentially the game, he claims, was rigged, and the American taxpayer paid for it all, and will pay again as the bubble is allowed to reflate. This time it’s when (not if) this bubble pops, according to Stockman, the unfortunate results will be much more serious. As with all of these types of prognostications, no one gives us a timetable, but his comments have some real meat to them.

The problem here is 20-20 hindsight, we all have it and it’s too easy to criticize. When you are in the eye of the storm, trying to keep what appears to be a collapsing global economy afloat, you make the best decisions possible at the time when the factors are not terribly pretty.

Multiple decisions were being made simultaneously hoping to stop the bleeding and keep things afloat. I suspect making sausage has that feel to it. I am not too interested in how it got on my plate, but it tastes good and does the job.

Stockman’s comments, in an article for the New York Times, are critical of the government’s continued running of the printing presses after the crisis. He also points out how hard it will be to get out the deep hole we are digging, especially when the time comes to turn off the spigot of Quantitative Easing (QE).

We remember back in 1994, when interest rates finally turned up, after what then seemed to be a long time at the super low level of 3 percent, and very soon we had multiple Fed interest rate increases priced into the bond market.

Stockman’s basic premise is we have created a massive impending disaster which, when it unfolds, will dramatically affect all asset prices. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke still seems to be parading around as if it’s all good, but does this emperor have any clothes?