By: Steve Sosnick, Chief Strategist IB

It seems like a quaint anachronism now, but Y2K was all too real for many of us. It was 25 years ago, right about now and in the days leading up to it, there was an undercurrent of concern, if not fear or dread, about unintended effects around the turn of the millennium. While many might say that the fears were unfounded, I’ll assert that the ho-hum reaction was because enough people had enough respect for the potential consequences and acted accordingly. Yet the stock market felt a nasty aftereffect…

The whole problem stemmed from an issue that now seems completely anachronistic. In an era where some of us routinely carry around as much as a terabyte of data in our pockets, it is nearly impossible to imagine that computer memory was precious and expensive. But look at an old movie, where computers took up whole rooms and were backed up by giant tapes or punch cards. Even by 1999 this was no longer the case, but significant amounts of legacy code that was written in that era were still in use. A common way that early programmers saved valuable memory was to refer to years as two-digit, not four-digit numbers. Early on, those two digits were a big resource saver.

The concern of course was that “00” was less than “99”. Another was that any program that utilized an equation with “00” could return “not a number”, or something else that caused the program to crash. Thus, a global effort to find and convert code that used two-digit years into four-digits years was implemented. Further complicating the effort, some of that code was written in somewhat forgotten languages which lacked proficient coders. I recall a bull market for programmers who knew COBOL, which was stably running many legacy systems but not readily edited by newer graduates.

I’d like to think that my experience was similar to that of others in the industry. We ran a complicated options market making model, which even then was highly reliant upon algorithmic trading. Our code was not nearly as obsolete, and many of the original programmers still had key roles in the company (some still do), so we were confident that our systems would operate properly. The problem was that we couldn’t be certain that the confidence of others wasn’t misplaced. What if one of the clearinghouses put the wrong settlement date on all our trades – or the whole industry’s for that matter? And of course, what if power plants or military systems froze up? Fortunately little, if any, of those fears came to pass. Key systems were properly adjusted, and life went on.

Yet the market implications of Y2K were felt for some time. The Federal Reserve had also prepared for Y2K. Not only did that include fixing their internal systems, they spent much of the latter part of 1999 adding liquidity to the financial system and making sure that the sudden increased demand for physical currency was met. (What if ATMs or credit cards were unavailable?) Those were prudent, and probably necessary, moves – except for the unintended consequences.

Bear in mind that we were in the midst of an unprecedented, technology-driven stock market rally that came to be known as the internet bubble. By late 1999, stocks were putting in yet another in a sequence of double-digit gains, propelled by enthusiasm for all things internet related. All things being equal, it is highly unlikely that the Fed would have aggressively added liquidity into a potentially overheated, “irrationally exuberant” market environment, but for the aforementioned reasons, it was necessary. Then when the crisis passed, the Fed began draining that excess liquidity from the system.

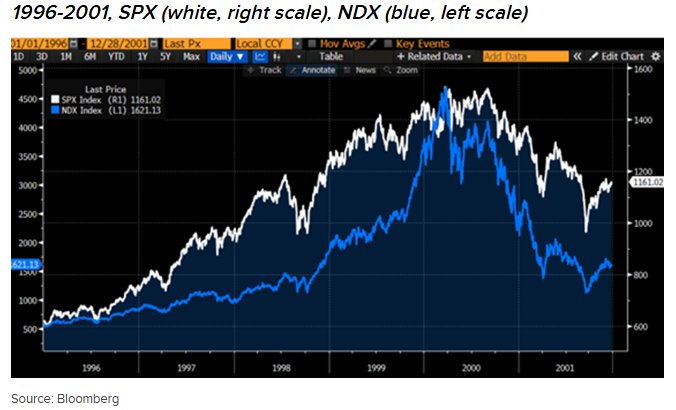

Unfortunately, a liquidity reduction was really the last thing an overenthusiastic market needed. The reaction didn’t happen immediately, though. The S&P 500 (SPX) peaked in August 2000, and the truly stellar performance of the tech-laden Nasdaq 100 (NDX) peaked in March. Stocks began to sink, in some cases sharply, throughout 2000 and 2001 (with 9/11 unfortunately exacerbating the decline in the latter year). In the chart below, note how steeply NDX rallied in late 1999 and how profound the eventual decline became.

Although many have drawn parallels between the internet bubble and today’s AI-fueled enthusiasm, the Y2K factor was a truly differentiating factor. History might rhyme, and while the outcome for stocks is never guaranteed, in this case, this portion of history certainly doesn’t repeat.

Originally posted on December 31, 2024 on Trader’s Insight

PHOTO CREDIT: https://www.shutterstock.com/g/sumeth711

VIA SHUTTERSTOCK

DISCLOSURES:

The analysis in this material is provided for information only and is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security. To the extent that this material discusses general market activity, industry or sector trends or other broad-based economic or political conditions, it should not be construed as research or investment advice. To the extent that it includes references to specific securities, commodities, currencies, or other instruments, those references do not constitute a recommendation by IBKR to buy, sell or hold such investments. This material does not and is not intended to take into account the particular financial conditions, investment objectives or requirements of individual customers. Before acting on this material, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, as necessary, seek professional advice.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Interactive Brokers, its affiliates, or its employees.