Kevin Flanagan, Head of Fixed Income Strategy

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s Jackson Hole speech has now come and gone, so the next big thing on the Fed calendar is the September 20 FOMC meeting. As expected, Powell didn’t offer up any groundbreaking headlines last week, but the overarching message from the chair still resounds loud and clear: rates will be “higher for longer.” That brings us to the next question: how high and how long?

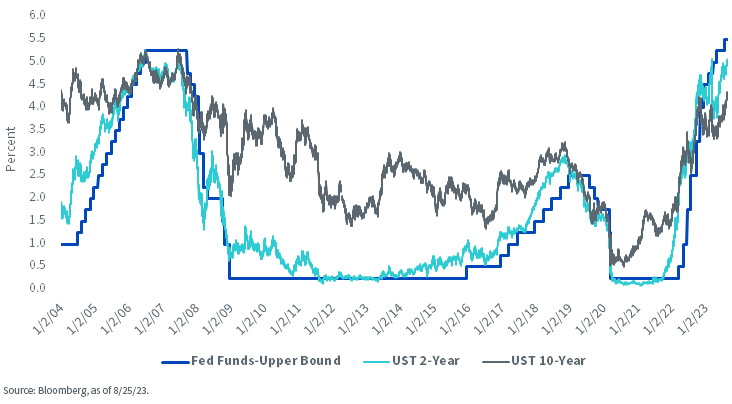

Fed Funds vs. Treasury Yields

As I’ve discussed quite a bit recently, the recent sell-off in the U.S. Treasury (UST) arena seems to underscore the point that the money and bond markets have finally “come to the Fed” and accepted this higher-for-longer theme. It certainly has taken a while, but I do wonder if UST yields have truly embraced just what that might entail.

Based on the two most recent rate hike cycles, one could conclude that further increases in UST yields should not be ruled out. Specifically, I’m referring to the Treasury 2- and 10-Year notes. The accompanying graph outlines how UST 2- and 10-Year yields typically rise to levels that are either at or above the Fed Funds’ upper bound, especially as we’re around the peak level.

Early on, this rate hike cycle did follow in history’s footsteps, but more recently, things have changed considerably. In fact, other than for a brief period in early March when the UST 2-Year yield was above the Fed Funds target, both these Treasury yields have actually been well below the Fed Funds rate this year. Indeed, at one point, the UST 2-Year yield traded nearly 125 basis points (bps) below the Fed Funds target, while the 10-Year was a whopping 170 bps under the upper bound.

While some of these inversions were a result of the regional bank turmoil, this negative spread relationship has continued some four to five months later. Yes, the latest increase in Treasury yields has narrowed the gap, but the inversions are still at -43 bps and -125 bps, respectively.

While there’s a debate within the Fed regarding whether to stay put or if another rate hike or two will be needed, both the “pause” and “hike” camps have one thing in common; rates will remain in restrictive territory for the foreseeable future. Against this backdrop, it does not seem unreasonable to expect that UST 2-and 10-Year yields could still rise further from current readings. In fact, the 2-Year has now moved back over the 5% threshold, while the 10-Year yield is at its highest level since 2007, placing it in somewhat uncharted territory.

Conclusion

That is not even factoring in this question: what if another quarter-point rate increase does happen at either the September or November FOMC meeting? Such a move would bring the upper bound of the Fed Funds trading range to 5.75%. Even if the Treasury 2- and 10-Year yields maintain their current inverted status relative to Fed Funds, another leg up in Treasury yields, at a minimum, should be considered.

This post first appeared on August 30th, 2023 on the WisdomTree blog

PHOTO CREDIT: https://www.shutterstock.com/g/chanawut13

Via SHUTTERSTOCK

DISCLOSURE

Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Diversification does not ensure a profit nor guarantee against a loss.

This material represents an assessment of the market environment at a specific point in time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events, or a guarantee of future results. This information is not intended to be individual or personalized investment or tax advice and should not be used for trading purposes. Please consult a financial advisor or tax professional for more information regarding your investment and/or tax situation.