Stock market booms and busts are only truly visible in hindsight. We never know if a given week’s broad market decline is just a “pullback” or the start of something bigger. Perhaps much bigger.

I was reminded of this recently when – in the midst of some housecleaning – I unearthed a trove of about 800 stock prospectuses. I’d accumulated these earlier in my career when I worked for other companies as a technology analyst and portfolio manager. Most of these related to the initial public offerings of tech companies between 1998 and 2001.

Thumbing through these prospectuses was a head trip. A journey with a few familiar names like eBay and Yahoo and many, many more names long forgotten. Click Commerce. Bindview. BAM! Entertainment. Don’t feel bad: I’d forgotten them too. Normally when you mention a public company in a column like this, the lawyers make sure you mention a company’s ticker symbol and price. Mostly unnecessary here: virtually no company represented via these prospectuses still exists, let alone are still publicly traded.

20 Years Ago

So here we are, coming up on 20 years since an infamous market top. The puncturing of the dot-com bubble. It took more than 2 ½ years for the tech-heavy NASDAQ Composite index to fall from 5048.62 on March 10, 2000 to 1114.11 on October 9, 2002, an astounding 78% decline.

In November 2002, 40% of the portfolio managers and analysts at the money management firm where I ran a tech mutual fund were fired. Dozens lost their jobs. I felt lucky to survive.

So what can we learn today in 2020 from the past?

- Deals come in waves. Looking through my pile of prospectuses, I see lots of copycat deals. Linux pioneer Red Hat went public on August 11, 1999 and was quickly followed by VA Linux, Andover.net and Caldera. A bunch of portable power systems players go out (Beacon Power, H Power, Active Power, Capstone Turbine). Business-to-business Internet commerce gets its day. Ariba, PurchasePro, Fairmarket and CommerceOne, all went public in a 12 month stretch of 1999-2000).

My experience is that the first IPO in an industry tends to have the most solid financials and the quality declines from there. But there are exceptions.

Search Engines

A wave of search engines (About.com, AltaVista, Lycos, LookSmart, Ask Jeeves) went public in the late 1990s but Google (2004) vanquished them all. More recently, there has been a wave of network security companies. Which will survive?

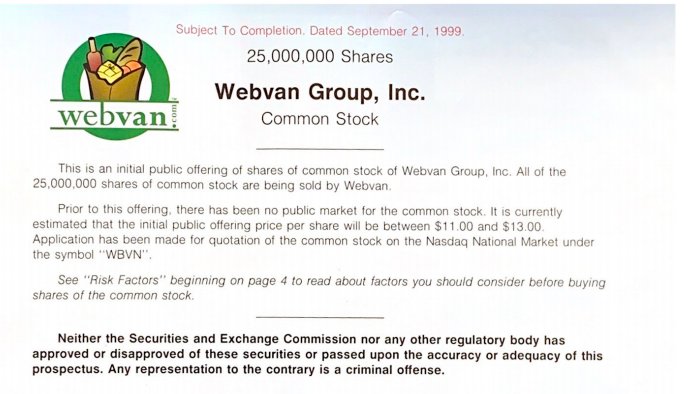

- Beware the conventional wisdom that the dot-com era was all bad. Sure, many of us remember object lessons like Pets.com (with its sock monkey spokespuppet), Webvan and eToys. Companies that were born to be punch lines for investors and the financial media. Some of the companies went public with a “going concern” letter from their auditors – almost unthinkable a few years earlier.

But some academics at the University of Maryland determined the survival rate for venture-backed companies in the late 1990s was no worse than the historical average up to that point. And that the ones who survived weren’t merely the name brands of today, but profitable niche players unknown then and now.

- Predictions aren’t worth much. As of January 2020, the current bull market is nearly 11 years old. Can the dot.com era tell us when the good times will end? Let’s let former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan answer that. Back in the 1990s, Greenspan warned that “irrational exuberance” – powered by dot-com speculation – meant it was likely the stock markets were then over-valued. That may have been true, but he said that on December 5, 1996. The NASDAQ Composite index closed at 1,300.12 that day. Over the next three and a quarter years, it rose 288%. Then, as now, markets reach new highs by going up…past old highs. And not always exuberantly.

For me, the dot-com era involved a lot of hotel food, as my peers and I sat through hundreds of road show presentations by giddy soon-to-be-temporary millionaires. By late 1999, due diligence had devolved to two simple questions: 1) “Who has the books?” and 2) “How hot is the deal?”

Takeaway

If Morgan Stanley or Robertson Stephens was the lead underwriter, you were – in theory – in good hands. And if the deal was at least 10x oversubscribed early in the road show, it was safe to bid yourself. Of course, hindsight tells us that the good times ended, new securities regulations were passed, and many investment banks, like Robertson Stephens itself, went out of business. In the end, IPO could have stood for “It’s pretty outrageous.”

So what happened to my prospectus collection? It went into our recycling bin. Except for the memories, prospectuses don’t seem to have much value, judging by eBay and bullmarketgifts.com (which itself seems like a dot-com survivor, don’t you think?).

For me, the fondest memory of 1999 was the birth of my son in May of that year. That IPO was a blue-chip keeper.

Photo Credit: Clint Mason via Flickr Creative Commons