By Steven Levine, Senior Market Analyst at Interactive Brokers

The allure of higher yielding, U.S. dollar-denominated corporate bonds has led to a massive spike in issuance volumes, along with heightened risks of refinancing failures and potential defaults.

Demand for corporate debt has generally continued unabated, especially among those global bond investors who have been seeking the yield offered in the U.S. primary market – having been priced out of their local markets or have a dearth of available paper.

In fact, the value of global bonds with negative yields stood at US$13.4trn at the end of October, having risen as high as US$17trn a few months earlier, according to Vanguard Investments.

“That means investors around the world have been willing to pay a premium to corporations or countries for the privilege of lending them money,” Vanguard said.

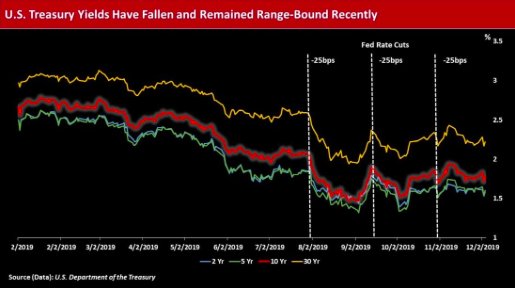

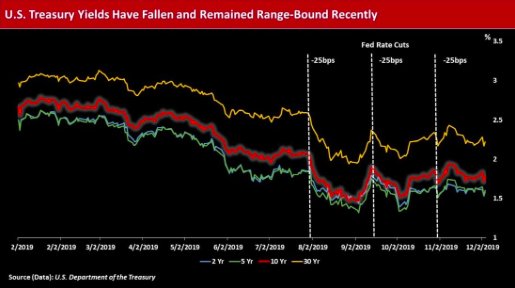

Sovereign Bonds

Indeed, sovereign bonds in several developed economies have seen most, if not all, of their yield curves residing in negative territory, including Germany, Switzerland and The Netherlands.

The levels fall against a backdrop of ultra-low, zero or negative interest-rate policies at a host of global central banks – aimed at stoking stubbornly low levels of inflation in their respective territories and enabling less expensive export prices to help grow their economies.

For example, the Bank of Japan (BoJ), the Swiss National Bank (SNB) and Sweden’s Riskbank have maintained policy rates at extremely low or negative levels at least since December 2008. Main policy rates at the BoJ and SNB currently stand at -0.10% and -0.75%, respectively, while the Riskbank and the European Central Bank (ECB) are at -0.25% and 0.00%, respectively.

IMF Forecast

However, the central banks’ strategies generally do not appear to be helping.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), for example, had lowered its global growth outlook to 3.0% for 2019, its lowest level since 2008–09 and a 0.3% downgrade from the April 2019 WEO.

The Washington, D.C.-based organization underscored how manufacturing activity has “weakened substantially” – to levels not seen since the global financial crisis – while increasing trade and geopolitical tensions have promoted greater uncertainty over the future of the global trading system and international cooperation more generally, “taking a toll on business confidence, investment decisions, and global trade.”

The IMF added that while increased monetary policy accommodation has “cushioned” the impact of these tensions on financial market sentiment and activity, its overall outlook “remains precarious.”

Relative Outlier

Meanwhile, relatively higher levels of interest rates at the Federal Reserve have frequently spurred condemnation by U.S. President Donald Trump, who recently tweeted the Fed “should lower rates (there is almost no inflation) and loosen, making us competitive with other nations.”

Market participants have been generally scrutinizing the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) for their stance on monetary policy this past year, after U.S.-China trade tensions, slowing global growth, weak domestic fixed investment and sluggish inflation helped reverse their hawkish agenda – and instead spurred a trio of rate cuts.

The latest decision by the FOMC to slash the target range for the federal funds rate by another 25 basis points to 1.50%-1.75% is widely expected to remain in place, at least through year-end.

As the committee gets set to release their next monetary policy decision at the conclusion to its two-day meeting on Wednesday, December 11, recent quotes about the future implied probability the central bank will elect to keep rates in the 1.50%-1.75% range were just north of 96.5%, with the small remainder anticipating a 25bp hike.

Credit Quality

Against this landscape, the lower rate environment, combined with several variations of quantitative easing (QE) measures at certain central banks, including the Fed, the ECB and the BoJ, have spurred investors to assume more risk.

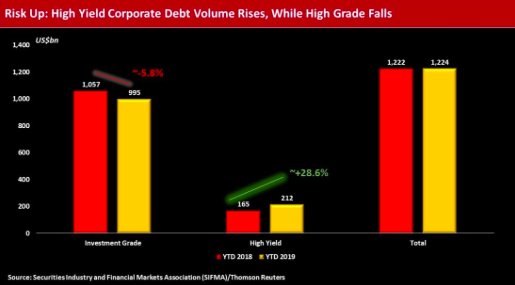

To date in 2019, U.S. high yield corporate debt issuance volume has soared 28.6% to US$212.4bn year-over-year, while investment-grade quality corporate bonds have fallen by around 5.8% to US$995.2bn over the same period, according to SIFMA researchers and data sourced by Thomson Reuters.

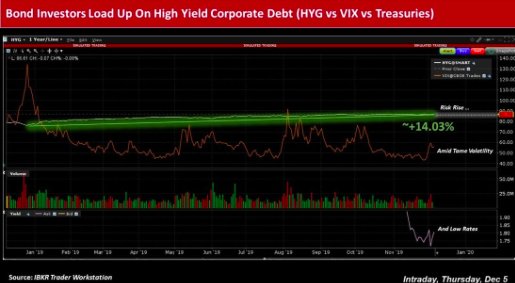

Bond investors’ rabid demand for high yield corporate bonds seems apparent, given the asset class’s total returns of roughly 14% year-to-date in 2019, compared to about 15% for high grade corporates and 7.4% for U.S. Treasuries.

Analysts at Janney Montgomery observed that triple-‘C’ rated corporates, “which have been a laggard in taxable fixed income total returns year-to-date,” saw 0.5% returns Wednesday over the prior day’s trading session “to bolster all of high yield, though other ratings categories helped as well.”

Capital Flows

Moreover, for the week ended November 27, Thomson Reuters/Lipper U.S. Fund Flows posted net inflows into high yield funds of around US$348m, with investment grade corporate fund inflows amounting to more than US$4.5bn.

Also, the iShares iBoxx High Yield Corporate Bond exchange-traded fund (ETF / NYSEARCA: HYG) has risen a little more than 14% since its latest 52-week trough of around US$75.96 set on December 24, 2018, amid lower rates and tame volatility.

Overall, analysts have warned about the uptick of riskier assets at bond mutual funds, where total assets under management (AUM) appear to have more than doubled in the past ten years, and which represent about one-tenth of the entire corporate bond market.

In her congressional testimony in September, Federal Reserve governor Lael Brainard pointed out that yields on high yield corporate bonds, relative to U.S. Treasury securities, “remain somewhat narrow on a historical basis despite recent increases.”

She highlighted that in addition to generating losses for investors, declines in valuations “could make it more challenging for firms to obtain or extend financing—especially among risky, indebted firms—which in turn could be amplified by the high levels of risky corporate debt.”

Brainard added:

“Both economic theory and econometric evidence point to the risk that excesses in corporate debt markets could amplify adverse shocks and contribute to job losses. Over-indebted businesses may face payment strains when earnings fall unexpectedly, and they may respond by pulling back on employment and investment. The slowdown in activity lowers investor demand for risky assets, thereby raising spreads and depressing valuations. As business losses accumulate, and delinquencies and defaults rise, banks are less willing or able to lend. This dynamic feeds on itself, potentially amplifying downside risks into more serious financial stresses or a downturn.”

Warning Signs

Fitch Ratings recently noted that its ‘Top Bonds of Concern’ list grew to US$48.4bn in November from US$33bn in the prior month, with Community Health Systems (NYSE: CYH) producing the lion’s share of the increase.

While Fitch’s trailing 12-months (TTM) U.S. high yield default rate for November stood at 2.6%, unchanged from October 31, it remained the highest level in nearly a year.

Fitch said it expects the rate to approach 3% by year-end 2019 “if the handful of announced distressed debt exchange (DDE) offerings are completed,” notably a US$2.6bn offer by Community Health, and if Panamanian construction company McDermott International (NYSE: MDR) fails to make its interest payment by its December 1 grace period expiration.

In the meantime, issuers of high yield corporate bonds continue to sell new offerings, amid sufficiently calm market conditions.

Photo Credit: Zooey via Flickr Creative Commons