High beta stocks are the Sofia Vergaras of the investing world: Unquestionably sexy, and as much as you may like it to be the case, probably not your best friend.

In fact, there is a good deal of academic research that says it’s the low-beta names that will outperform over the long haul. That flies in the face of the long-held theory that investors are paid to take on extra risk.

“As an investor, getting the low and high-beta concept is important,” says Bill DeShurko of 401 Advisor, a Covestor model manager. “And if your portfolio has been up to this point, you really need to look at beta, understand it, and consider some of the low- beta holdings.”

First, a quick refresher:

Beta measures the relative volatility of a stock or a portfolio. A beta of 1 means that the stock or portfolio can be expected to move right along with the stock market.

A stock with a beta of 1.5 is 50% more volatile than the market. A stock beta of 0.8 is 20% less volatile than the market.

Most stocks have betas that are fairly close the mean, although there are some with wild extremes. Biotech company Vanda Pharmaceuticals (VNDA) has a very high beta of 8.1 (more than 8 times the market volatility). The electric utility Consolidated Edison (ED) has one of the lowest, less than 0.1 (or 10% the market volatility).

In all fairness, market participants choose high-beta and low-beta stocks for all sorts of reasons.

High-beta seems to be advantageous in secular bull markets: Low volatility stocks underperformed from 1990 to 1999, for example.

And some traders will purposely seek out high betas. The expected movement based on chart patterns can be bigger, and tend to happen quicker.

Low-beta names, though, have become popular recently. Some like DeShurko see low-beta investments as a way to still stay invested while being a bit more cautious.

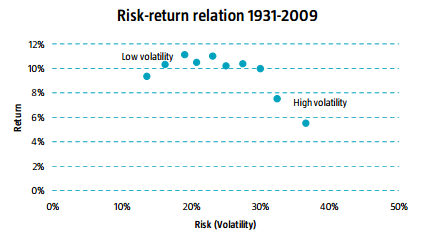

There is something else to consider too: The chart below comes from a detailed report from portfolio manager Pim van Vliet at Robeco:

Source: Robeco.com

Van Vliet’s chart shows the average compounded return of portfolios sorted by volatility and beta from 1931 to 2009.

Over that 80-year span, low-beta stocks offered better risk-reward ratios and a superior return versus high-beta stocks. It’ s a conclusion that flat-out contradicts the theory that risk and reward are correlated!

Others have observed this phenomenon, as well. Tadas Viskanta at Abnormal Returns dedicated an entire chapter to low-beta investing in his new book.

“It’s foolish to buy and hold the high-beta sections of the market,” DeShurko says. “Why would you want to hold something with higher risk that underpeforms the market just for the diversification? Strangely, that’s what your typical financial planner and 401k providers would tell you to do.”

High-beta stock movements may be driven by the desire for a fast buck, or perhaps a sort of gambling. Research analyst Dylan Grice thinks investors systematically overpay for high-beta stocks because they simply dig the thrill.

My thought on this is that traders of the high-beta names may be willing to overpay for high beta because they are more interested in momentum and the completion of technical patterns that become self-fulfilling prophecy.

Super-sized valuations are sometimes tolerated as long as there are no hiccups to the stock story. But those high-beta names trading on technicals are often routed after patterns are completed, or at the first moderate signs of disappointment.

Knowing all the research about how low-beta stocks perform better over the long haul, DeShurko still plays them both — an America Ferrara (aka Ugly Betty) meets Sofia Veragra strategy, of sorts.

He tends to invest in high-beta stocks during the November through April time periods, then favors low-beta names when it’s time to sell in May and go away.

“What I’ve found is that the seasonality is strong, and foolish to ignore, DeShurko says. “So we will be looking to rotate into lower-beta stocks as we enter the weaker half of the year. There is no question.”