Climate change is a maddenly complex subject. Yet it’s useful to think about in terms of three numbers: 1.2, 1.5 and 2.0.

Despite more than two decades worth of global climate conferences like the COP26 gathering now underway in Glasgow, the world has failed to tap down the growth in greenhouse gases that are heating up the planet and destabilizing weather patterns.

At the COP21 conference in Paris back in 2015, 195 nations signed a landmark agreement to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit that increase to 1.5°C.

Where are we now?

Record Heat

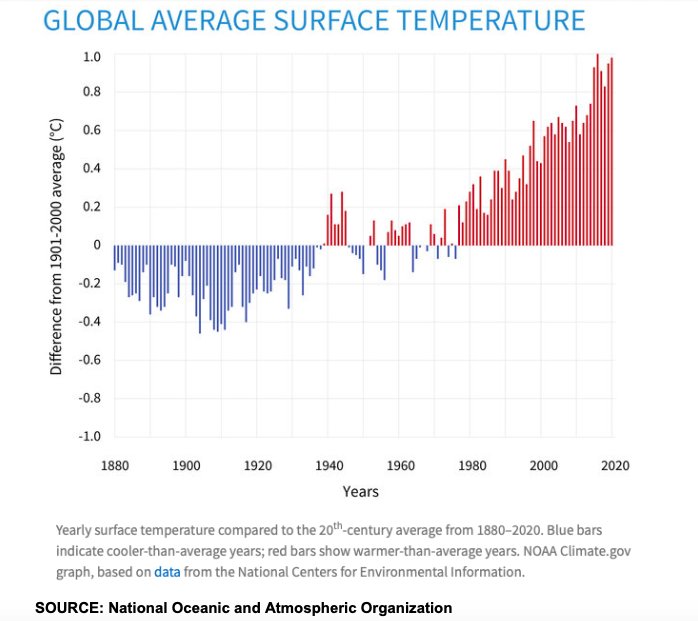

In 2020, one of the warmest years on record, global temperatures hit 1.2ºC (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

Last year, there were a record number of hurricanes, wildfires and floods amplified by climate change that cost the global economy some $210 billion in damage, data compiled in a report by reinsurance company Munich Re showed.

The climate change price tag in the US hit $95 billion, double the level in 2019, thanks to a record number of Atlantic hurricanes and wildfires in California.

In the first half of 2021, we’ve seen severe heat waves in North America’s Pacific Northwest and historic flooding in Germany.

Climate Stakes

A world that warms to 1.5°C is now considered a pretty aspirational target. Yet even if global economies decarbonized quickly enough to hit that goal, the climate impact would still be negative.

If we slip to 2.0°C or more, the risk of a climate breakdown increases markedly, according to research by climate scientists.

Consider the following: With a 1.5°C increase, extreme hot days in the mid-latitudes of the planet will be 3°C hotter (5.4°F) than pre-industrial levels. A 2°C increase, translates into about 4°C hotter (7.2°F) than pre-industrial levels.

Sea levels are expected to rise by about 0.26 to 0.77 meters (0.85-2.52 feet) relative to the average from 1986-2005 by 2100. If you’re looking at a 2°C increase, sea levels are projected to rise by 2100 by 0.36 to 0.87 meters (1.18-2.85 feet) during the same period.

Takeaway

With an 1.5°C increase, the Arctic Ocean will become ice-free in the summer about once every 100 years. It’s once every 10 years at a 2°C increase.

Managing the tradeoffs between the economic hit of an overheated planet and shifting away from a multi-trillion dollar fossil fuel industry is a challenging one for political leaders, business executives and investors.

Yet if you want to know what’s at stake, 1.2, 1.5 and 2.0 are the numbers to keep an eye on.

Photo Credit: GPA Photo Archive via Flickr Creative Commons

DISCLOSURE

This piece is provided as educational information only and is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument, or to participate in any particular trading strategy.