By Fong Yee, senior product manager, sustainable investing

Carbon intensive sectors are facing unprecedented scrutiny from governments, regulators and markets. Since this can have a significant impact on liquidity and asset values—indeed, the effects are already becoming visible—it is a factor that investors cannot afford to ignore. The real estate sector, which is characterized by long-lived and energy-intensive assets, is one such target.

The U.N. estimates that buildings account for over half of global electricity usage, about 28% of global carbon emissions and over 10% of potable water consumption. To keep global warming below 2 degrees as mandated by the Paris Agreement, the real estate sector alone will need to reduce total CO2 emissions to 36% by 2030.[1]

As policy makers try to accelerate emission reductions across entire economies, building stock with poor environmental performance is a likely target for new policy measures. This creates significant policy risk for real estate investors who, in a worst-case scenario, could see substantial reductions in asset values and liquidity.

This is happening now: UK landlords can no longer let residential or commercial buildings with F- or G-rated energy performance certificates. New York City’s Building Emissions law (Local Law 97) aims to cut emissions from buildings by 40% (by 2030) by placing a cap on carbon emissions for buildings over 25,000 sq. ft. (2,300 sq m2). The UN-backed Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) expects decisive government policy measures globally by 2025 and has highlighted how these measures will have a clear impact on businesses and their investors.[2]

It’s not necessarily bad news, though. In contrast to other carbon intensive industries, the real estate sector benefits from a range of cost-effective, well-understood solutions to reduce energy use and achieve carbon savings. Furthermore, there’s also a growing body of evidence suggesting that strong sustainability performance contributes to better branding and higher asset values in the sector. Several recent studies see a correlation between greener buildings and higher occupancy rates, higher rental values and reductions in operating costs.[3]

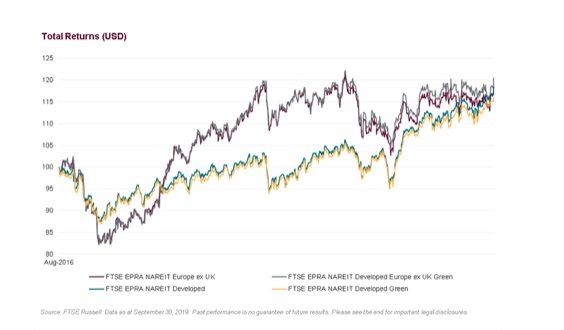

Our own analysis suggests that investors can be exposed to green real estate portfolios while limiting downside risk. The performance of the FTSE EPRA Nareit Green Real Estate Index Series, for example, suggests green real estate has provided increased exposure to real estate portfolios demonstrating strong sustainability performance while minimizing tracking error versus the market cap benchmark.

Challenges remain at the portfolio level as investor-focused tools for real estate have been limited. Unlike listed equities and, to a lesser extent, bonds, property investors have lacked comprehensive data that allows them to systematically factor climate concerns into real estate investment portfolios. Ultimately this is a problem of disclosure, and whereas listed companies increasingly provide information on ESG issues to investors, real estate companies lag other sectors.

Market leaders often disclose third-party assured data across a range of sustainability considerations but most do not.[4] As an example, less than half of the largest 50 constituents of the FTSE EPRA Nareit Developed Index, which is designed to represent general trends in eligible real estate equities worldwide, report their carbon emissions.[5] Disclosure levels will have to improve as investors demand better data. The industry will also need to develop innovative, alternative approaches to assessing real estate portfolios where data gaps remain.

Pressure for change, therefore, won’t just come from the policy angle. Investors are setting increasingly ambitious sustainability targets across their investment strategy and asset allocation and capital is starting to shift towards more sustainable assets/mandates. This will accelerate as data and financial products become more available.

To avoid the risk of drawing conclusions from a single (albeit lengthy) time period, we can also look at value/growth performance cycles over shorter holding periods to assess the persistence of the value premium over shorter time frames.

Examining excess returns to value stocks over rolling 3 year holding periods shows that the value premium is not assured over shorter time horizons.

Dot.com Era

After experiencing a positive premium throughout most of the 1980s and the mid-1990s, value stocks began underperforming growth stocks by a large margin as valuations of companies driving the “new economy” were driven to unrealistic levels.

After the bubble burst in the early 2000s value experienced a resurgence, with a cumulative performance premium over twice that of growth. As the economy recovered this premium began to diminish and reversed in the late 2000s.

The value premium started to make a comeback after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009 but this was short lived as the US entered a prolonged bull market phase, and growth stocks began outperformance value stocks consistently.

So what is an investor to do? For those who believe the value premium will rise again, the best approach may be patience. The ability to weather market cycles can be rewarding. For others who don’t have the wherewithal or conviction to wait, perhaps the best approach would be to balance their portfolio between growth and value stocks in consideration of the natural diversification that this provides.

This post first appeared on November 6 on the FTSE Russell blog.

Photo Credit: Charles Knowles via Flickr Creative Commons

© 2019 London Stock Exchange Group plc and its applicable group undertakings (the “LSE Group”).

All information is provided for information purposes only. All information and data contained in this publication is obtained by the LSE Group, from sources believed by it to be accurate and reliable. Because of the possibility of human and mechanical error as well as other factors, however, such information and data is provided “as is” without warranty of any kind.

No member of the LSE Group nor their respective directors, officers, employees, partners or licensors make any claim, prediction, warranty or representation whatsoever, expressly or impliedly, either as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness, merchantability of any information or of results to be obtained from the use of FTSE Russell indexes or research or the fitness or suitability of the FTSE Russell indexes or research for any particular purpose to which they might be put.

Any representation of historical data accessible through FTSE Russell indexes or research is provided for information purposes only and is not a reliable indicator of future performance. No member of the LSE Group nor their respective directors, officers, employees, partners or licensors provide investment advice and nothing contained in this document or accessible through FTSE Russell Indexes, including statistical data and industry reports, should be taken as constituting financial or investment advice or a financial promotion.