By Jay Jacobs, CFA; Pedro Palandrani; Chelsea Rodstrom; and Rohan Reddy, Global X

Big Tech companies like Amazon, Google, and Facebook have come to dominate their respective corners of the industry, like e-commerce, search, and social media. Many believe that consumers have benefited, as these giants offer many frequently used services that are either free or low cost.

Yet at the same time, regulators and consumer advocates are beginning to question whether it is in the country’s and society’s best interest to allow these companies to maintain their dominance. Concerns over how these companies have acquired and protected consumer data, policed the content on their platforms, and stifled competition have led to louder calls to regulate or even break up these Big Tech names.

In this piece, we look at historical examples of antitrust regulation, the current state of Big Tech regulation, and explore various policy approaches that could be implemented in the space.

A Historical Look at Antitrust Regulation

Federal antitrust law dates back to 1890, when Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act to curb monopolistic business practices and promote competitive free markets.

The Act was relied upon to dismantle turn-of-the-century giants like Standard Oil and American Tobacco Company. Since then, thousands of antitrust cases have been opened by the Department of Justice, with 22 cases thus far in 2019, but rarely do they result in industry-changing breakups.

One of the most important antitrust rulings, and one that has parallels to today’s environment, was the “1956 Consent Decree” against American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T)’s Bell System. At the time, AT&T controlled and facilitated 98% and 85% of all long and short distance telephone services, respectively, having a tight hold on the nation’s communications industry.1

Big Bell

Further, AT&T bought its telecommunications equipment from its manufacturing subsidiary Western Electric, which produced equipment based on research from Bell Labs, the research subsidiary of AT&T. All of this together formed a corporate powerhouse called the Bell System.

Rather than breaking up the company initially, the 1956 Consent Decree forced AT&T to share its patents with other companies for free and prohibited the firm from entering other industries, like the budding computer industry.

This approach was designed to spur innovation and competition by allowing smaller companies to access Bell System’s leading intellectual property in areas such as transistors, solar cells, and lasers. During the next five years, around 1,000 new patents cited Bell Labs’ technologies as foundation for inventions, demonstrating the successful approach.2

Nevertheless, antitrust concerns continued to pressure regulators and in 1984, AT&T was broken into eight separate ‘Baby Bells’. AT&T kept its long-distance telephone services, but spun-out their local services for each Baby Bell. The breakup, however, failed to yield much innovation or competition. Each Baby Bell remained a local monopoly, and it only took a few years to see numerous consolidations in the industry, largely reversing the breakups.

While just one example, AT&T’s antitrust history shows that efforts to reduce monopolistic power may have various intentional and unintentional consequences that must be carefully considered prior to enacting new regulations.

What’s been happening recently?

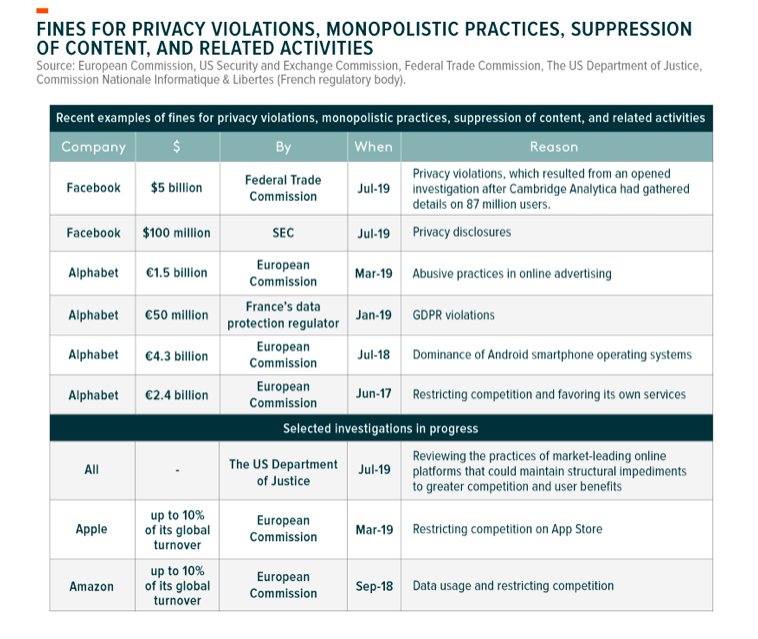

Fast forward to today, policy makers are beginning to take a more aggressive stance towards Big Tech, levying fines, proposing laws, and conducting investigations into firms’ business models and practices. Below are some recent efforts to investigate and punish major tech names.

The House Judiciary Committee opened a bipartisan inquiry into the power and practices of major technology companies

- The Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission recently decided to divide responsibility for potential antitrust investigations. The Justice Department is taking Google and Apple, while the F.T.C. has Facebook and Amazon.

Record fines are being levied, particularly in Europe, which has taken a more aggressive stance on privacy and promoting competition:

What are the possible ways Big Tech could be regulated?

Regulating Big Tech presents a host of challenges for policymakers. On one hand, these companies have driven enormous growth and disruption, heralding in a new era of information technology and communications.

On the other hand, many argue this growth has come at the expense of competition, data privacy, and content quality. In an ideal world, any regulation would seek to accelerate competition, innovation, and growth, while implementing stronger protections for consumer data and effectively policing content. Below, we look at various potential forms of regulation, considering the benefits and challenges to each approach.

Keep Big Tech Companies Intact but Promote Self-Regulation

Social media companies are already self-regulating, deciding which accounts to delete and suspend, and which posts to block for inappropriate or hateful content. Yet this network policing is happening at the individual firm level, with each social media company setting and enforcing their own policies and procedures.

In a growing industry with little to no external regulation, social media companies are often forced to choose between profitability or privacy and content quality. Policing a network to improve quality is not only a major expense in headcount and technology, but also a drag on revenue, as fiery content must be removed that could have grabbed millions of impressions. YouTube, for example, has 10,000 people working on monitoring and deleting content, removing nearly 100,000 videos each day.3 Therefore, while social media companies may want only the highest quality accounts and content on their networks, the cost of achieving this goal may be too high for firms to voluntarily stomach.

One route to consider is the creation of a self-regulatory organization (SRO) overseeing the social media industry; a concept familiar to the financial industry with SROs like FINRA, the New York Stock Exchange, and the Options Clearing Corporation. By establishing an SRO, the social media industry could create a central governing body that sets policy on acceptable content, policing sites, and protecting users’ data and privacy. These policies would be enacted evenly across the industry to help create a level playing field and improve transparency for end-users.

For an SRO to be successful though, it must have the ability to set rigorous and comprehensive rules, as well as enforce them. As non-government agencies, SROs tend to have more flexibility in creating and updating rules – a welcome advantage for a rapidly changing industry. Yet without government backing, powerful enforcement tools are key. A social media SRO would need to have the ability to audit firms and their practices, levy fines on firms with infractions, and hold individuals accountable.

Staffing the SRO with high quality personnel, adequately funding the organization, and getting buy-in from a government organization like the FTC would also help with establishing a successful self-governing approach to the social media industry. An SRO must also carefully consider how its policies affect both large and small companies so as not to inadvertently stifle competition from smaller players with less resources.

Force the Breakup of Big Tech Firms

Like AT&T in 1984, many are proposing to reduce the monopolistic power of Big Tech by breaking these firms into numerous independent businesses. Advocates for this approach believe tech companies have become too powerful, often buying up, copying, or limiting accessibility to potential threats. As such, less concentrated power could increase competition, resulting in further innovation and value for consumers. An anticipated downside of this approach is greater inefficiency, as each ‘baby tech’ firm would need its own organizational infrastructure and support, as well as have a higher cost of capital.

A breakup would also result in substantial questions about how to divvy up the data aggregated across platforms. Can Facebook separate the data acquired from Instagram versus WhatsApp versus Facebook? Each resulting baby tech company would fight for the most data possible, like firms from a dismantled oil conglomerate would fight for wells.

Chris Hughes, Facebook’s co-founder, who left the company in 2007, has now become a proponent of splitting Instagram and WhatsApp from Facebook. Some of his arguments hold that privacy and data security has been sacrificed for growth. Competition has suffered too, with over 2.7 billion people around the world using at least one of Facebook’s Apps, while there hasn’t been a major social media company founded in years.

The same concerns apply to Google’s control over search and online advertising, Apple’s apps through their App Store, and Amazon’s hold on the e-commerce landscape. With all these companies now looking to enter new markets and industries, like driverless cars, virtual and augmented reality, and original content, efforts to limit their dominance continues to grow.

Turn Big Tech’s data into a public utility

Another approach is to treat data as a public utility. In the United States, utility companies are heavily regulated as the government recognizes their monopolistic status. The government understands it’s inefficient to have multiple utility companies operating in the same area, especially because of the significant capital spending needed to serve consumers. In order to rein in the power of these utilities, prices are often set by local, state, or the federal government to target a specific level of profitability.

This brings us to tech companies and their data. Like utilities, tech companies have become essential to our lives, with online shopping, search, and content sharing becoming as routine as turning on the faucet for water. Policymakers could take the position that Big Tech is an essential service and that monopolistic characteristics are preferable, but should be regulated. Instead of having multiple companies collecting, storing and attempting to protect data, one carefully regulated utility could centralize this function to reduce redundant costs and put in place one robust solution for data protection. Under such an approach, Facebook, Google, and Amazon would no longer own proprietary data on individuals, but would have to apply for a license to ‘rent’ the data from the utility based on preset rates and would only be entitled to certain information.

While this approach is relatively unique, in theory it would lower the moats Big Tech has created around their businesses with proprietary data collection, thereby increasing competition and enhancing privacy protections. Opponents of such an approach would likely argue that utilities are often inefficient due to a lack of competition, and the forced seizure of Big Tech’s data, akin to eminent domain, is a major government overstep.

Data Taxes

An effective use of taxes is to disincentivize unwanted behavior. Much like the current approach of fining Big Tech firms for privacy infractions, data taxes could be levied to raise the cost of data collection for major data owners, which would help level the playing field for smaller players.

A parallel for this approach can be drawn to professional sports. In most major professional sports leagues a salary cap or luxury taxes limits or disincentivizes teams from spending significantly more than others. Such an approach is designed to limit the power of ‘super teams’, while redistributing the wealth to poorer teams. In practice, data taxes could be used to effectively limit the data collected by major tech players, and use the proceeds to invest in tangential areas, like 5G infrastructure, computer science education, or small business loans.

The challenge with data taxes is that the benefit to consumers is indirect and could even back-fire. Raising the cost of data collection could ultimately be passed along to consumers, who may no longer enjoy free photo storage, email, and search.

How China is Approaching Big TechIt’s important to note that Big Tech’s competition is no longer just a battle within Silicon Valley, but a global race to dominance. Regulators in China have garnered attention for overlooking and implicitly supporting megamergers to create tech behemoths that compete with US technology firms in areas like electric and autonomous vehicles, 5G, and artificial intelligence.

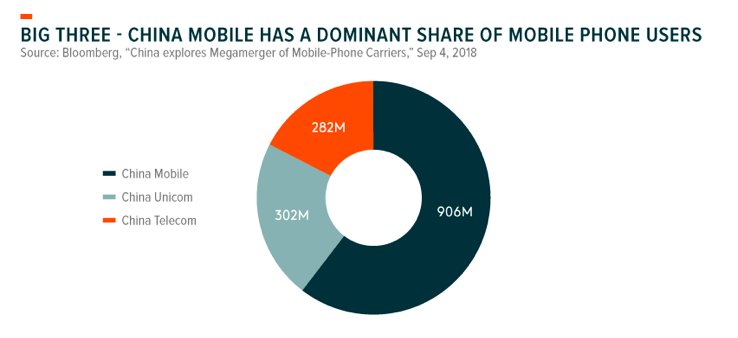

Last year, for example, news broke that Chinese authorities were considering a megamerger between its largest carriers, which could bulwark national investments in 5G.

The merger would combine China United Network Communications Group Co. and China Telecommunications Corp, leaving the merged entity to directly compete with China’s largest telecom provider. The entity, majority-state-owned China Mobile, is one of the largest telecoms companies globally and one of the largest companies by market cap in China’s broader Communication Services sector.

Given the massive size of China’s market, with over 1 billion subscribers, and the rapid pace of adoption, a merger could help China’s tech industry scale quickly and compete for global dominance despite a period of escalating trade tensions. Certainly, merger approval would reflect the Chinese government’s relentless commitment to developing next generation technologies that compete with US Big Tech firms.

At the same time, a megamerger could lead to a bloated firm with operational inefficiencies, reduce local competition, and potentially higher prices. Spillover effects could harm areas critical to China’s long-term strategy, with elevated prices borne by tower providers, information technology firms, health care providers, or consumers, hindering domestic growth. Awareness of these structural challenges, which could undermine Chinese efforts to lead in 5G, are likely behind the protracted approval process by state authorities.

Conclusion

Antitrust scrutiny of some of the largest companies in the world – and vital for the US economy – should be viewed as one of the most influential factors a government can have on its economy.

New policies to regulate the tech space could impact employment, growth, and even national security given the gravity of the global tech arms race. For Big Tech firms, even if no immediate resolution is reached, it could result in distractions, dampening innovation. It is important that policymakers and regulators carefully consider each of these factors and create an optimal solution that promotes innovation and growth while protecting consumers.

Reference Shelf

1. Yale, “How antitrust enforcement can spur innovation: Bell Labs and the 1956 Consent Decree,” Jan 9, 2017

2. Ibid.

3. BBC, “Social Media: How Can Governments Regulate it?” Apr 8, 2019.

This article appeared in the Global X Research & Insights blog on August 13, 2019:

Photo Credit: Chris Urbanowicz via Flickr Creative Commons

Disclosure:

Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. International investments may involve risk of capital loss from unfavorable fluctuation in currency values, from differences in generally accepted accounting principles, or from economic or political instability in other nations. Emerging markets involve heightened risks related to the same factors as well as increased volatility and lower trading volume. Securities focusing on a single country and narrowly focused investments may be subject to higher volatility. CHIQ is non-diversified.

Certain of the information contained in this article is based upon forward-looking statements, information and opinions, including descriptions of anticipated market changes and expectations of future activity. These statements are based upon a number of assumptions concerning future conditions that ultimately may prove to be inaccurate. The author believes that such statements, information, and opinions are based upon reasonable estimates and assumptions. However, forward-looking statements, information and opinions are inherently uncertain and actual events or results may differ materially from those reflected in the forward-looking statements. Such forward-looking assessments are subject to risks and uncertainties and may be affected by various factors that may cause actual results to differ materially. Therefore, undue reliance should not be placed on such forward-looking statements, information and opinions.

This information is not intended to be individual or personalized investment or tax advice and should not be used for trading purposes. Please consult a financial advisor or tax professional for more information regarding your investment and/or tax situation. Information provided by Global X Management Company, LLC (Global X) and SEI Investments Distribution Co. (SIDCO). Global X and SIDCO are not affiliated.