Two years ago, I took a long look at the 3D printing industry. It was a time of great hope for 3D printing, with the advent of newer, cheaper models like those offered by MakerBot.

It was an exciting time for shareholders in companies like 3D Systems (DDD) and Stratasys (SSYS), whose stock prices had risen considerably in 2012; and it was exciting for investment bankers, as they prepared to take Voxeljet (VJET) and ExOne (XONE) public in early 2013.

Pricey

But after I analyzed the industry and its investment opportunity, I came to two conclusions.

First, that the stock prices of DDD, SSYS carried premium valuations that seemed to reflect that a mass consumer market for 3D printing was just around the corner. I said, “no way.”

Secondly, the state of the 3D printing industry/ecosystem in early 2013 eerily resembled the mini-computer business in the 1980s.

Back then, Digital Equipment, Wang Labs and Apollo Computer were whistling past the graveyard as cheap ‘WinTel’ PCs destroyed their businesses from the inside out.

3D Systems and Stratasys were making the bulk of their revenue and profit from $100,000 machines and consumable resins. So I wondered two years ago how long their profit margins could hold up with dozens of capable machines being offered for as little as $1,000?

3D landscape

For merely suggesting that all was not rosy on 3D Planet, I was subjected to all manner of abuse by readers. I was flat-out “wrong.” I was “narrow in thought and short-sighted.”

There was “nothing positive to say” about my conclusions. But let’s see now how short-sighted I was. Or wasn’t.

First off, then as now, I fully understand the importance of 3D printing to the world of commercial manufacturing. In short, there’s been a revolution in the way product development takes place, enabled by the rapid prototyping of pre-production parts.

Moreover, 3D printing has enabled the manufacture of low-volume parts, like turbine blades, where traditional processes were inadequate to the task.

Mass market illusion

But the mass market and the assumed huge increase in revenue and profits that would have justified premium multiples have failed to arrive. According to market research firm Gartner, only about 108,000 3D printers were sold worldwide in 2014.

That’s one printer for every 65,000 people on earth. By comparison, 2014 global mobile handset sales totaled 2.1 billion – or roughly 19,400 handsets for every 3D printer. Even IDC, which is extremely excited about 3D printing, expects only 310,000 3D printers to be sold in 2017.

So let’s look at the trajectories of the two major publicly-traded 3D printing vendors, DDD and SSYS since I wrote my column.

In mid-January 2013, the consensus estimate for Stratasys’s 2013 earnings per share was $1.93. At that time, SSYS shares were trading at $86, giving the company a one-year forward P:E multiple of 45.

As I write this in mid-January 2015, SSYS is expected to earn about 50% more ($2.94) in 2015, but its valuation has collapsed to a forward P:E of only 26.3. At about $77/share, SSYS shares are lower now than they were two years ago.

Lackluster returns

In fairness, SSYS shares have been higher during the intervening two years, but nonetheless are lower now. By comparison, the S&P 500 is up 38% in that time frame.

3D Systems has fared even worse. Two years ago it traded at $63/share with a forward multiple of 40.5. Today its multiple (26.3) and its earnings expectations have collapsed and the company trades at only $32/share.

I’m not going to take a victory lap over this. As I noted, prices for these stocks have been higher in the past two years. Maybe you somehow managed to buy low in 2012 and sell high two years later.

If so, then good for you. No, the takeaway for investors is how a decaying high valuation becomes a return-killing headwind when over-the-moon expectations aren’t fulfilled. Even for companies like Stratasys whose earnings have actually increased.

And unless you’re particularly good at market timing, you’re probably going to lose money in that scenario.

So what about my other assertion: that the emergence of capable yet far less expensive 3D printers would cannibalize higher-end “enterprise” models? It’s fair to say the jury is still out on that dynamic.

I’m supported in my belief by Gartner, which in an October 2014 industry report wrote it expects “more organizations [will] employ low-end and midrange printers for testing and experimenting.”

Specifically, Gartner believes such experimentation will cause the sub-$1,000 3D printer segment to grow from 11.6% of the market today to 28% by 2018.

Microsoft of 3D?

But there has yet to emerge a Microsoft-type player in the 3D printing space – an independent, well-funded company with a compelling value proposition ready to Trojan Horse their way into established manufacturers.

MakerBot, a New York City-based company that began selling very low cost (~$1,000) 3D printers in 2009 might have been the one, but it was bought by Stratasys in 2013 in order to instantly provide the larger company with a line of “consumer” printers.

There are, however, no shortage of other potential disruptors. Make: magazine, perhaps the unofficial print organ of the 3D printing enthusiast community, reviewed no less than 26 low-cost printers in its most recent annual round-up – up from only 15 printers two years ago. And the recent and forthcoming expiration of key patents governing 3D printing will only lower prices and barriers-to-entry even more.

The bottom line: I still think that 3D printing will never be a mass consumer market…and it seems with the re-valuation of 3D printing stocks in the past 24 months, many other investors agree with me.

There’s no reason why 3D Systems, Stratasys and other public and private vendors of 3D printers can’t thrive and provide value to their customers. But their stock prices are likely to remain at risk from ongoing pricing pressure and ever-lower barriers to entry.

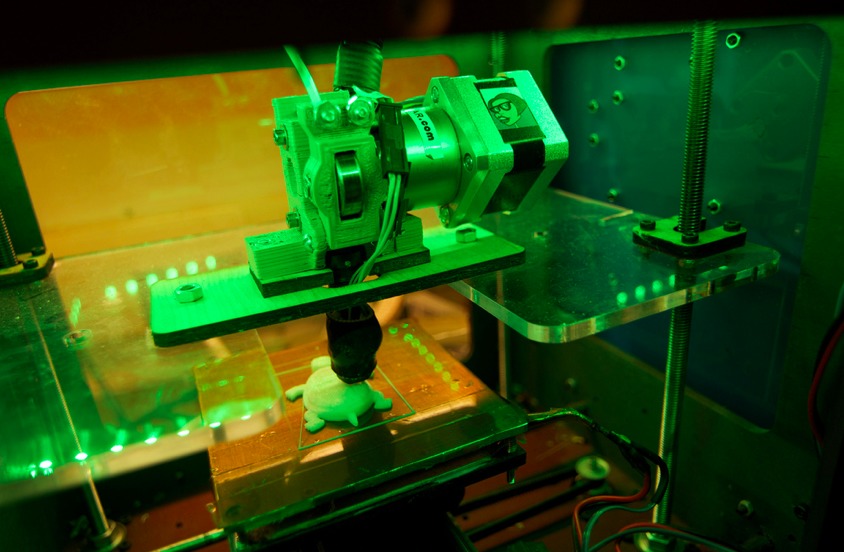

Photo credit: Keith Kissel via Flickr Creative Commons

DISCLAIMER: The investments discussed are held in client accounts as of December 31, 2014. These investments may or may not be currently held in client accounts. The reader should not assume that any investments identified were or will be profitable or that any investment recommendations or investment decisions we make in the future will be profitable. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.