By one important measure, the U.S stock market is looking overvalued, warns my former colleague Mark Hulbert, who writes the Hulbert on Markets column for Barron’s.

The high valuation, however, does not necessarily suggest that stocks cannot continue to make gains toward the end of the year.

Mark is an important voice in the financial world, as has some uncommon tools in his stocks toolbox. The bulk of his analysis comes from his more than 30-year career tracking the sentiment of the newsletter writers and pointing to opportunities when their opinions reach extremes.

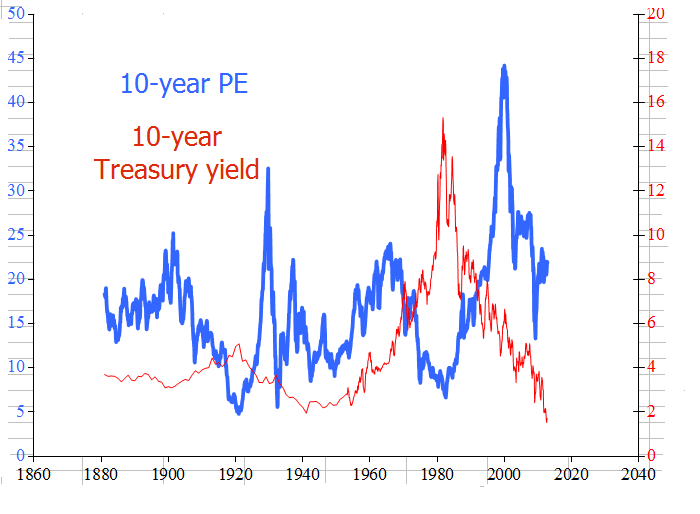

His latest worry, though is not with what the newsletter writers are saying: It’s the straight-up expense of stocks based on 10-year PE, a measure made popular by Yale economist Robert Shiller.

It’s the straight-up expense of stocks based on 10-year PE

Current PE and even forward PE measures have limitations. They can be heavily influenced in the short-term by the E part of the equation — or short-term distortions in a company’s earnings. A sudden drop in E, and a company can look very expensive — even though the E drop may be tied to macroeconomic cycles, or only for a short period of time. Similarly, a very strong earnings period that is not necessarily sustainable can make a stock look cheap.

An arguably better goal for the long-term investor is to look at companies with a steady long-term earnings track record, then focus in on the times when the Ps, or prices, are historically weak or strong.

That’s what a 10-year PE lets you do. It takes the current price, divided by a 10-year stream of inflation-adjusted earnings. It allows you to then look at the periods when price is at a long-term discount, or the times when you want to be careful not to overload on stocks because they are at a long-term premium.

Source: Online data, Robert Shiller

As Hulbert notes, stocks are arguably on the expensive side based on that important measure. Today’s 10-year PE ratio, as calculated by Shiller is 20.2, higher than the long-term average of 16.5. Meanwhile, the current S&P 500 dividend yield is around 2%, less than half the historical average of 4.4%.

The upshot is that the 10-year PE is higher than 77% of its readings since 1881. And as Mark notes, stocks are nearly 10% more overvalued based on 10-year PE than the average past bull market when it came to an end.

Shiller’s data seems to make the case that future long-term gains may be limited.

There are some other points to consider, though:

- For starters, past market tops did not happen in an environment when the Fed was encouraging risk-taking in stocks with its monetary policies. The installation of QE3 has relatively few historical comparisons, but analyst John Kozey keeps his advice simple: It’s not a good idea to fight the Fed right now; the valuations may go even higher.

- We already are past September, historically the worst-performing month of the year. And while October also tends to be volatile, we also are entering a historically strong season for stocks. According to research by Ben Jacobsen and Cherry Yi Zhang, the average difference between November-April and May-October returns is 6.25% over the past 50 years. Based on that history, at least, it’s more likely a time to buy, not sell.

- A lot of near-term market direction will depend on third-quarter earnings reports. They might not be pretty, but the good new is that expectations already have come down greatly. Eighty out of the 103 S&P 500 companies that have given earnings guidance, or 78%, have issued a third-quarter forecast that falls below the Wall Street consensus estimate, according to FactSet Research. Guidance hasn’t been worse since FactSet started tracking earnings warnings in 2006. A historically strong reaction to bring down estimates may help to limit downside surprises.