by Michael Tarsala

Comparisons of the latest troubles at Chesapeake (CHK) to the notorious frauds at Worldcom and Enron are misplaced for two reasons:

- To date, there’s been no fraud found at Chesapeake

- Fraud gives investors few, if any, warning signs

But in Chesapeake’s case, the red flags were right there. As Reuters reported, CEO Aubrey McClendon was moonlighting as a hedge fund manager and trading the same commodities that CHK produces. There are now calls for a Justice Dept. review – in addition to an ongoing IRS audit.

Here are the 3 red flags that might have helped detect early trouble. They’re actually a set of questions that can be applied to any large stock holding, for that matter:

1) Know the reasons for stock underperformance.

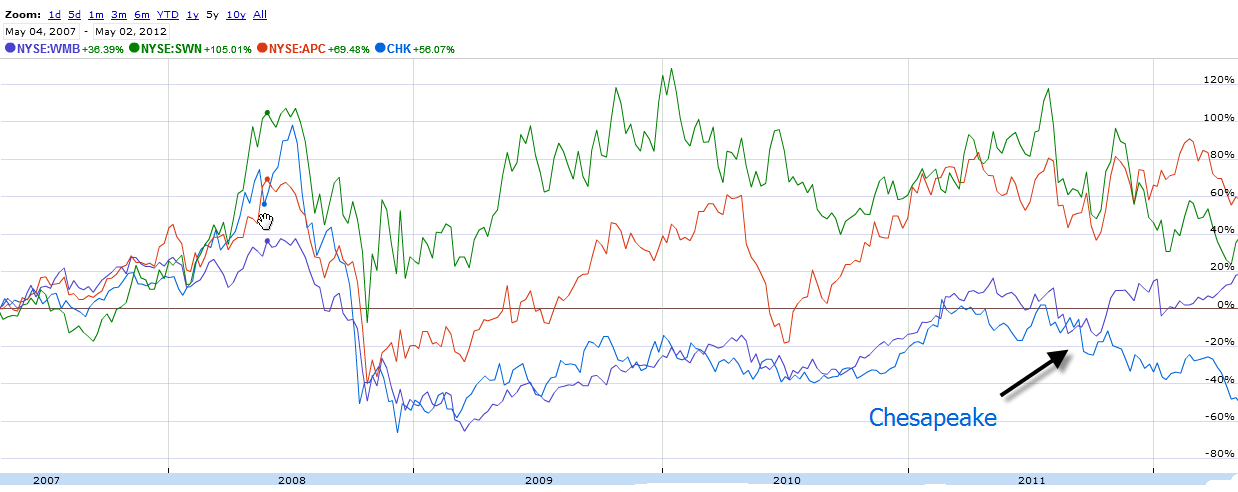

Source: Google Finance

Chesapeake is the No.2 gas producer in the U.S. You can its stock chart relative to peers, above. It’s underperformed for most of the past 5 years – not just in recent months.

Lots of stocks have problems and can still be suitable investments.

But there are reasons so-called “value” stocks trade at deep discounts. It’s important to understand those reasons.

In Chesapeake’s case, its discount is due largely to its high debt levels, a business model that some argue is tied more to land ownership than drilling, and subsequent concerns about management. All of that was known before the latest news broke.

2) Look at debt ratios, not just earnings and price ratios.

Exploration and production takes capital. So nearly every company in the industry has debt. But few are like Chesapeake. At the end of last year, it had $351 mln of cash on its books, and more than $10.5 mln in debt. The company has carried even higher long-term debt levels – often with even less cash – for each of the past 5 years. Reducing debt is now one of the company’s biggest challenges– something it is expected to achieve by selling off assets. Debt has been an ongoing issue.

3) When the road gets rocky, watch out for more rocks

What else might be discovered about Chesapeake’s CEO?

That is a question everyone should have been asking back in March, when Rolling Stone started digging into Chesapeake’s business model, and reminded readers that he’s perhaps an unusual risk-taker — at least as far as CEOs go. Back in 2008, he had to liquidate much of his company stock to meet a personal margin call.

That question also could have been asked a bit more in April, when Reuters reported that McClendon had taken out up to $1.1 bln in loans against his stakes in Chesapeake oil and gas wells, a story that renewed questions about the company’s management team and board oversight.