By Kevin Flanagan, Head of Fixed Income Strategy

I haven’t had to blog about LIBOR and any attendant funding issues for a while … and that was the good news. Unfortunately, the negative market effects from the COVID-19 pandemic created a setting in the funding arena that needed to be addressed posthaste. The Federal Reserve (Fed) has thus far come to the rescue to avoid another financial crisis, realizing how vital it is to prevent another meltdown from a funding perspective.

We can all opine about how the Fed dropped rates to zero and kick-started its quantitative easing (QE) policy, but in my mind, the key was always to make sure that the financial world, companies and others could fund themselves. The concern is not really about debt that matures in later years, but rather the ability for borrowers to meet their short-term debt service costs. As we saw during the financial crisis, once it becomes apparent that these funding needs cannot be met, the adverse setting has the potential to not just snowball but avalanche.

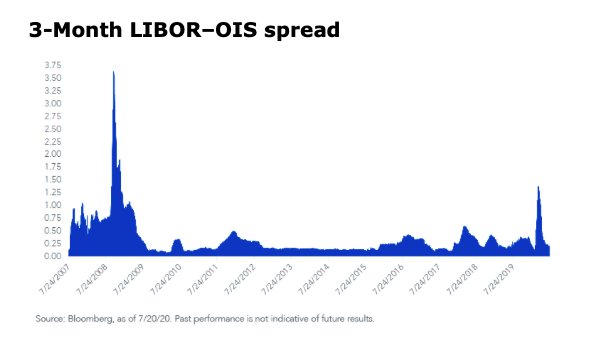

3-Month LIBOR–OIS spread

The focus of the money and bond markets has been on the 3-month LIBOR–OIS spread. We know LIBOR is a key borrowing benchmark rate. OIS (overnight indexed swap) is an interest rate swap that consists of both a fixed and floating rate component. The floating rate part uses an overnight rate index—in the case of the U.S. dollar, the Federal Funds Rate—while the fixed portion is set at a rate agreed upon by the two parties. Thus, the OIS is considered a proxy for Fed Funds. The LIBOR–OIS spread itself represents the difference between these two instruments and measures one rate that could contain potential credit risk (LIBOR) versus one that essentially does not (Fed Funds).

When this spread widens, it is considered to be a sign of stresses in the short-term bank funding markets. As the graph highlights, this spread widened to 138 basis points (bps) in March, the second highest reading on record. Interestingly, it still pales in comparison to the 364-bps peak during the financial crisis. But that’s the important point: the Fed reacted proactively, used its financial crisis playbook, added some new “wrinkles” and prevented a run at the all-time high. The good news doesn’t end there, however. The LIBOR–OIS spread has now fallen to roughly 20 bps, back to pre-pandemic levels.

Conclusion

Are we out of the woods? Perhaps being a bond guy, I remain cautious and will continue to monitor developments in the funding markets on a regular basis. Recent Fed commentary suggests that policy makers have a little bond guy in them as well. As a reminder, the FOMC is scheduled to meet Wednesday, July 29, and we’ll be sure to blog about the outcome, which more than likely will underscore the committee’s commitment to market normalization and economic support.

Unless otherwise stated, all data sourced is Bloomberg, as of July 20, 2020.

Photo Credit: Pictures of Money via Flickr Creative Commons

Disclosure: This publication may contain forward-looking assessments. These are based upon a number of assumptions concerning future conditions that ultimately may prove to be inaccurate. Such forward-looking assessments are subject to risks and uncertainties and may be affected by various factors that may cause actual results to differ materially.