By Robin Marshall, Director, Fixed Income, FTSE Russell

The sheer scale of the economic contraction caused by the coronavirus shock and Great Lockdown is emerging (although much still depends on the length of the Lockdowns, unemployment levels, business survival rates and how far consumer behavior adjusts).

For example, the IMF now projects the Great Lockdown contraction as the greatest since the 1930s depression, dwarfing the great financial crisis (GFC) recession, with an estimate of -3% global growth in 2020 vs only -0.1% in 2009 (IMF, April 2020).

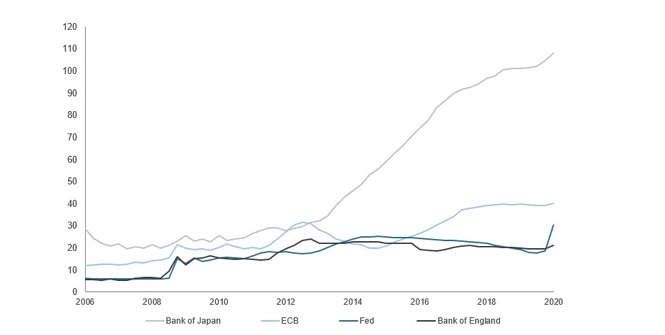

Some central banks have implicitly conceded marginal changes to the QE programs used in the GFC are unlikely to restore acceptable levels of employment and inflation. Therefore, both the Fed and ECB have now broadened their QE asset purchases to include lower grade corporate credit. But these changes still remain modest given the IMF is forecasting an output loss of about $9 trillion in the global economy from Covid-19. At least central banks have a balance-sheet room to expand QE programs substantially.

Central bank balance sheets as a % of GDP

Source: FTSE Russell / Refinitiv. Data as of April 2020.

…forcing policy makers to consider responses on a scale previously unimaginable

Given high debt/GDP ratios, alternatives to debt-financed fiscal stimulus, like helicopter money (fiscal stimulus financed by printing money), have been raised (see FTSE Russell blog post on Helicopter Money.) Theoretically, central banks are not limited in the amount of extra reserves they can create, so this could be done on a huge scale to finance government stimulus.

For the EU, where the IMF is forecasting a contraction of 7.5% in 2020, but the impact of the shock is uneven, the urgency of the joint policy response is driven by the existential threat to the future of the Eurozone posed by the shock. ECB President Christine Lagarde has already proposed some form of coronavirus bonds be issued by Eurozone members, and the Spanish government has proposed a €1.5 trillion perpetual coronavirus bond in the Eurozone to finance economic recovery.

Helicopter money raises governance and moral hazard concerns

But moving beyond debt-financed fiscal stimulus and QE programs raises issues of governance and moral hazard*. Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey has declared the BoE will not be financing central government through helicopter money because “Using monetary financing would damage credibility on controlling inflation by eroding operational independence” (Financial Times, April 5, 2020). But there is evidence from the UK central government’s Ways and Means Facility that it is already using money from the BoE to finance expenditures (just as it did during the GFC, on a modest scale).

But central banks could impose strict conditions on the money financing of government

The concern about governance and moral hazard with helicopter money is that without appropriate checks and balances, governments may use central bank money printing to finance reckless expenditures, jeopardising the economy and currency (as in Zimbabwe). Yet there is no reason why proper governance cannot be introduced, with the central bank controlling the process, just as central banks currently control QE programs.

Strict conditions could be imposed on how, and when this emergency central government account at the central bank could be used, including reference to the inflation target, and financial stability. Central banks already come very close to monetary finance of central governments in QE programs, buying government bonds. The main difference being that this is designed to be temporary finance, to be unwound in future, as opposed to a permanent increase in the money stock in helicopter money. After a massive deflationary shock to global demand, it could be argued economic conditions for helicopter money, with appropriate governance controls, are appropriate.

Some moral hazard may be inevitable, if central banks are to do enough to meet the challenge

The scale of the global policy challenge means trade-offs for policy makers between adopting more radical policy, like helicopter money, to restore economic stability, and the risk of moral hazard, are becoming more acute. Already, extending QE purchases to corporate bonds, including sub-IG bonds, means central banks have accepted some deterioration in the asset quality of their purchases and an increase in moral hazard.

Buying equities as part of QE, and a move to full-blown helicopter money would extend these risks and the moral hazard. But erring on the side of doing too little and allowing economic conditions to spiral downwards in a self-feeding contraction, like the 1930s, might carry even higher risks.

Photo Credit: Goddard Space Flight Center via Flickr Creative Commons

*Moral hazard is defined as a situation in which an individual has an incentive to increase their exposure to risk, because they do not bear the full cost of that exposure.

© 2020 London Stock Exchange Group plc and its applicable group undertakings (the “LSE Group”). The LSE Group includes (1) FTSE International Limited (“FTSE”), (2) Frank Russell Company (“Russell”), (3) FTSE Global Debt Capital Markets Inc. and FTSE Global Debt Capital Markets Limited (together, “FTSE Canada”), (4) MTSNext Limited (“MTSNext”), (5) Mergent, Inc. (“Mergent”), (6) FTSE Fixed Income LLC (“FTSE FI”), (7) The Yield Book Inc (“YB”) and (8) Beyond Ratings S.A.S. (“BR”). All rights reserved.

FTSE Russell® is a trading name of FTSE, Russell, FTSE Canada, MTSNext, Mergent, FTSE FI, YB and BR. “FTSE®”, “Russell®”, “FTSE Russell®”, “MTS®”, “FTSE4Good®”, “ICB®”, “Mergent®”, “The Yield Book®”, “Beyond Ratings®” and all other trademarks and service marks used herein (whether registered or unregistered) are trademarks and/or service marks owned or licensed by the applicable member of the LSE Group or their respective licensors and are owned, or used under licence, by FTSE, Russell, MTSNext, FTSE Canada, Mergent, FTSE FI, YB or BR. FTSE International Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority as a benchmark administrator.

All information is provided for information purposes only. All information and data contained in this publication is obtained by the LSE Group, from sources believed by it to be accurate and reliable. Because of the possibility of human and mechanical error as well as other factors, however, such information and data is provided “as is” without warranty of any kind. No member of the LSE Group nor their respective directors, officers, employees, partners or licensors make any claim, prediction, warranty or representation whatsoever, expressly or impliedly, either as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness, merchantability of any information or of results to be obtained from the use of FTSE Russell products, including but not limited to indexes, data and analytics, or the fitness or suitability of the FTSE Russell products for any particular purpose to which they might be put. Any representation of historical data accessible through FTSE Russell products is provided for information purposes only and is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

No responsibility or liability can be accepted by any member of the LSE Group nor their respective directors, officers, employees, partners or licensors for (a) any loss or damage in whole or in part caused by, resulting from, or relating to any error (negligent or otherwise) or other circumstance involved in procuring, collecting, compiling, interpreting, analysing, editing, transcribing, transmitting, communicating or delivering any such information or data or from use of this document or links to this document or (b) any direct, indirect, special, consequential or incidental damages whatsoever, even if any member of the LSE Group is advised in advance of the possibility of such damages, resulting from the use of, or inability to use, such information.

No member of the LSE Group nor their respective directors, officers, employees, partners or licensors provide investment advice and nothing contained in this document or accessible through FTSE Russell Indexes, including statistical data and industry reports, should be taken as constituting financial or investment advice or a financial promotion.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Charts and graphs are provided for illustrative purposes only. Index returns shown may not represent the results of the actual trading of investable assets. Certain returns shown may reflect back-tested performance. All performance presented prior to the index inception date is back-tested performance. Back-tested performance is not actual performance, but is hypothetical. The back-test calculations are based on the same methodology that was in effect when the index was officially launched. However, back- tested data may reflect the application of the index methodology with the benefit of hindsight, and the historic calculations of an index may change from month to month based on revisions to the underlying economic data used in the calculation of the index.

This publication may contain forward-looking assessments. These are based upon a number of assumptions concerning future conditions that ultimately may prove to be inaccurate. Such forward-looking assessments are subject to risks and uncertainties and may be affected by various factors that may cause actual results to differ materially. No member of the LSE Group nor their licensors assume any duty to and do not undertake to update forward-looking assessments.

No part of this information may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the applicable member of the LSE Group. Use and distribution of the LSE Group data requires a licence from FTSE, Russell, FTSE Canada, MTSNext, Mergent, FTSE FI, YB and/or their respective licensors.