Author: Charles Sizemore

Author: Charles Sizemore

Covestor models: Sizemore Investment Letter and Tactical ETF, Strategic Growth Allocation

Mark Twain noted that there are lies, damned lies, and statistics – and nowhere is this truer than in the investment profession.

Don’t worry, this isn’t another story about crooked Wall Street bankers fleecing the public. There have been enough of those written already. This is an article about a far more dangerous form of deception: lying to yourself.

The lie, of course, is that you can get money for nothing, that it is possible—and even easy—to beat the market without doing any real work. (Plenty of investors “beat the market” by the way. But they do it by doing the exhaustive legwork that others won’t or can’t do, and by taking well-placed risks that others are afraid to take.)

Today, we’re going to take a look at a market cycle that, on the surface, sounds like it makes sense – but actually fails to stand up to anything resembling statistical scrutiny: the 4-Year Presidential Cycle.

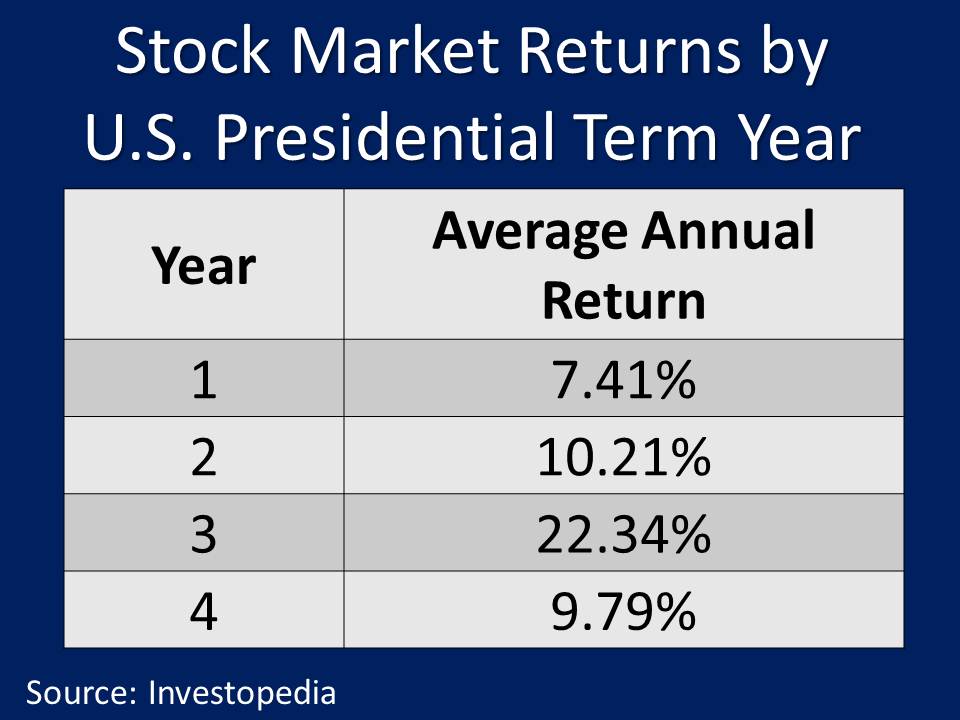

According to the theory, the stock market follows a predictable — and investable — 4-year cycle that coincides with the presidential term. Stocks tend to offer meager returns in the first two years of a presidential term but do particularly well in the third and fourth years. Presumably, this is because the growth policies that a president implements upon taking office take time to have their desired effect. And perhaps more cynically, a sitting president will pull out all of the stops to juice the economy in his last two years to make sure he gets reelected (or to make sure that his heir apparent gets elected).

All of this sounds great, of course. And the numbers would seem to support it. According to Investopedia, returns in year three are more than double those of any other year (see chart).

We’ll start with the obvious: the president of the United States may well be the most powerful man in the world, but he does not single-handedly control the economy or the capital markets. In the larger scheme of things, the White House isn’t all that important. It is American business and American capitalism that generate growth, not clever policy wonks in the Oval Office.

If you absolutely had to attribute market returns to the actions of one man, I would pick the Federal Reserve chairman over the president, due to the Fed chief’s control over interest rates. But the argument that a Fed chairman would use his power to help a sitting president never made a lot of sense. As often as not, the Fed chairman is of a different political party than the president. Why would a Republican Fed chairman try to get a Democrat president reelected (or vice versa)?

Now, let’s dig into the numbers. In the entire history of the United States of America there have only been 44 presidents and 56 presidential terms, and for the first 100 years of the republic there was no real stock market to speak of. The small number of traded stocks was hardly representative of the economy, which — outside of the northeast — was largely agrarian.

Being somewhat generous, we can say that we have usable stock market data starting around 1900. And since 1900 there have been 18 presidents and 27 presidential terms.

Anyone who suffered through college Statistics 101 would know that statistical analysis doesn’t work particularly well with sample sizes this small. The basic rule of thumb is that you need a sample size of at least 30 observations to draw meaningful conclusions.

In other words, the Presidential Cycle is statistical noise.

Investors should be wary of pet theories that view something as complex as the stock market through so simple a lens. Investing doesn’t have to be difficult, but it does involve work. Warren Buffett has made a career out of buying companies that are simple to understand, but he still does his homework. He reads the annual reports and picks through the numbers. And he certainly doesn’t put capital at risk based on astrology-like theories that market moves are preordained by the year of a presidential term.